It sounds strange, but sometimes threat groups in the dark web want to be seen.

Dark web publicity

The dark web gives us an insight into how threat groups organize and operate. This intelligence usually comes from catching cybercriminals out when they think they are acting under the radar (that is, afterall, why cybercriminals choose to congregate on the dark web).

However, somewhat paradoxically, this intelligence sometimes comes from messages and posts that threat groups want to be seen. That is because, in spite of their desire to evade attention from law enforcement, there is a counter need for them to communicate with others in order for their operations to be successful. Often, they need to communicate with other cybercriminals to collaborate, or to buy or sell goods. Sometimes they need to speak to their victims. Some groups (as we’ll see) are also reliant on publicity – and therefore have to disseminate information to the public and the press.

Therefore, while the individuals obscure their real names and identities with aliases, there is a lot of intelligence to be gained about the groups as a whole from their chosen communication methods.

We have selected the threat groups DarkSide and LAPSUS$ to illustrate this point. They make a good comparison: they both operated recently, both have ceased operations, both focused on “big game hunting”, and both relied on similar network intrusion tactics. Nonetheless, their dark web communication methods are a stark contrast from one another.

Darkside’s “professional” communications setup

DarkSide was a Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) group that amassed tens of victims in the period it operated (August 2020 – May 2021) but is most infamous for the Colonial Pipeline attack.

The group adopted what could be described as “traditional” communication methods for threat actors. It used its own dark web leak site (hosted on a Tor .onion address) and the Russian hacking forums XSS and Exploit, where it posted updates under the username “darksupp”.

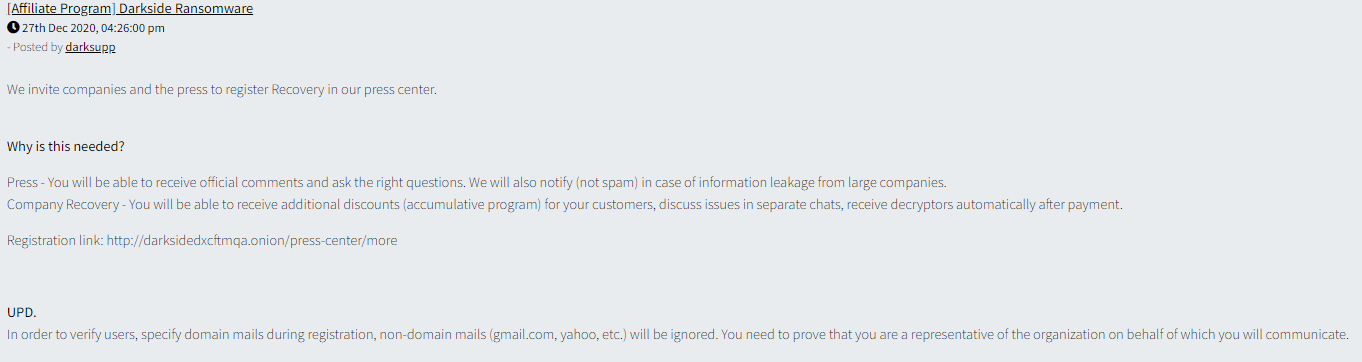

What distinguished DarkSide from other threat groups is how professionalized its communication setup became. For example, the “press center” the group established to share information with journalists and the organizations impacted by its operations, which it can be seen advertising below:

Furthermore, because the group began an affiliate program (offering its ransomware to third-party actors in return for a share of the profits) it adopted “customer facing” communication methods to share updates with its users and even address their issues and concerns.

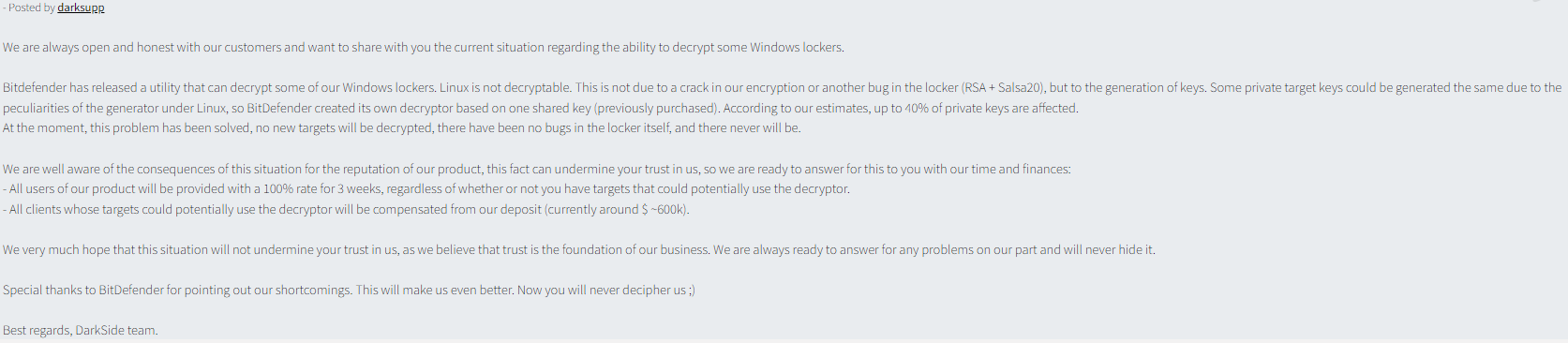

Take, for example, these posts communicating an update to its product following a decryptor released by Bitdefender that compromised some of the group’s operations. On January 12, 2021 the darksupp alias provided a thorough overview of the situation to reassure its customers that it was still trustworthy:

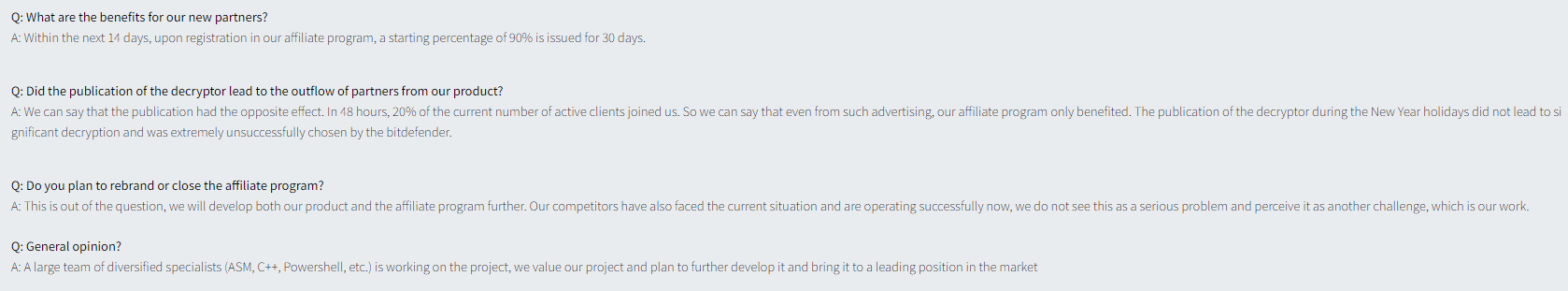

Four days later, it shared a Q&A on the product updates to answer its affiliates’ questions:

This communication is not only more professional than other RaaS groups, it also puts many enterprises’ customer service support to shame.

LAPSUS’ Unconventional approach to communication

It is safe to say that LAPSUS$ (which operated December 2021 – March 2022) took a less professional approach. In fact, one of the defining features of the group (other than its high profile targets, including Brazil’s health ministry, Impresa, Claro, Samsung, and Nvidia) was its unconventional communication methods and unorthodox tone, even by the standards of the cybercriminal community.

LAPSUS$ stood out initially for setting up a Telegram channel in December 2021 (shortly after the Brazilian health ministry hack), diverging from other groups who publicize their attacks on dark web sites. LAPSUS$ claimed responsibility for its attacks from this channel – for example, suggesting that it was responsible for an attack against Ubisoft by resharing a news story accompanied by a smirking emoji.

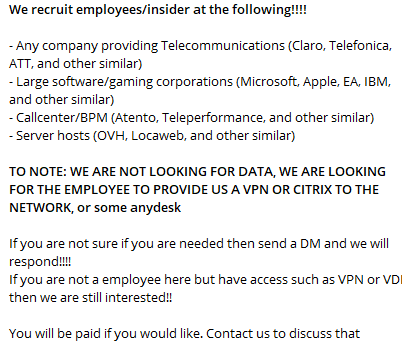

However, it also went further than that (and further than most other threat groups whose communication is usually limited to announcing, auctioning and sharing stolen data), by using its Telegram channel to crowdfund access to organizations. For example, putting out a recruitment call to malicious insiders at large telecommunication, software, call center, and server host firms:

While other actors do use insiders to compromise organizations’ defenses, these employees are typically sourced in a less conspicuous manner – such as over private messages – rather than on a public Telegram channel with 47,000 subscribers, in full view of law enforcement and security researchers.

In comparison to DarkSide’s efforts to win the trust of the cybercriminal community, LAPSUS$ was also more than happy to make some enemies as it became increasingly bold and outspoken.

For example, after a partial leak of data stolen from the software company Nvidia in February 2022, LAPSUS$ faced increasing calls from its followerbase to release the second half of the breach. After repeatedly assuring its followers that the data was forthcoming, LAPSUS$ changed tact – updating its Telegram channel “group rules” to include point 4: “Stop asking about NVIDIA”. It also missed another self-imposed deadline to release their alleged cache of Vodafone data, much to the ire of its followers.

Gathering adversarial intelligence

The differences between groups is more than just a point of interest. Understanding where and how threat actors communicate can help organizations gain valuable adversarial intelligence. This can be seen with both LAPSUS$ and DarkSide.

LAPSUS$’ Telegram channel provided information that helped better understand the group’s methods and operation. For example, initial reports that LAPSUS$ was a ransomware gang were proved false when LAPSUS$ itself stated on their channel “we said it was a ransom, not a ransomWARE”. Security researchers subsequently classified LAPSUS$ as a data extortion actor – one which breaches corporate networks, exfiltrates sensitive data and demands a ransom in return for not leaking the information online.

Meanwhile, DarkSide’s communication with its affiliates stated the “rules” of the program, with the group forbidding its partners from targeting certain industries, including healthcare, funeral services, education, public sector and non-profits, for “ethical” reasons. Those watching closely at the time might have spotted a warning sign that attacks were going to escalate when in March 2021 – approximately one month before the initial compromise of Colonial Pipeline – it announced a change to its affiliate program on the Exploit Forum, removing layers of “bureaucracy” and allowing its affiliates to “make calls” without asking the ransomware operators.

This demonstrates the opportunity presented by threat actors’ need to communicate. Monitoring these conversations and messages on the deep and dark web allows organizations to build a profile of their adversaries, to better understand their tactics, techniques and procedures. They can use this pre-attack intelligence to inform their cybersecurity strategy, building their defenses on a more accurate understanding of the threats they are facing.